Patricia Sullivan’s history of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a book every American should read. My review below the fold.

I was born in 1952. I grew up on a small farm in New Jersey. My parents and three brothers and three sisters and I resided on the second floor of a small farmhouse; my paternal grandfather, an immigrant from Finland, and grandmother, an immigrant from Ireland, lived on the first floor.

One night in 1964 I was watching television with my grandfather, and as I recall — the details are a bit foggy — we stayed up until way past midnight, watching the debate and vote on the floor of the Senate about the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

My grandfather’s invitation, in his heavy Finnish accent, went something like this. “You stay up and watch this, Yonny. Now we gonna see if the United States is full of beans or not.” When the bill passed, he said something like, “Well, OK. I guess not full of beans.”

I didn’t know many black people growing up, but I grew up in an anti-racist house. My parents taught us that any person was as good as any other, and my grandfather was a man of strong egalitarian principles. I really don’t recall encountering racism until I was a teenager, and the first time I heard anybody tell a “nigger joke” I was deeply shocked. I remember who said it, and where, and what he looked like. I was a 16 year old volunteer firefighter standing on the back of a fire truck en route to a brush fire –we did things differently back then–and the guy next to me was my father’s age. It was four days after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and that’s what his so-called “joke” was about. I suppose my shock was just a measure of how sheltered my upbringing had been.

I remember being young and reading about the March on Washington and hearing the news reports of the Freedom Riders; I remember the church bombings and the assassination of Medgar Evers and the sit-ins and the Selma fire hoses, and I remember being appalled and mystified. I knew things were different “in the South”. I guess I thought of it as a foreign place, like Russia.

But like most white Americans that I know, I never understood anything of the depth of the horribleness of the Jim Crow regime from the end of Reconstruction through the passage of the Voting Rights Act, when, arguably, things finally began to improve for Americans of African descent. I was also generally ignorant of the history of the Civil Rights movement. I thought that it more or less started with Rosa Parks in 1955, and that if you knew the general outlines of the “Eyes on the Prize” story from 1955 to 1965, you pretty much knew the whole story.

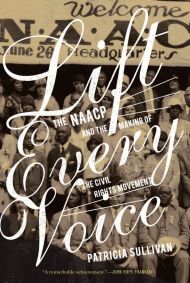

Having now read Patricia Sullivan’s magisterial Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement,

which chronicles the NAACP from its founding in 1909 through the passage of the laws of 1964 and 1965, I can tell you that until about a month ago I was fundamentally ignorant of American history, and that anybody who hasn’t read her book (or who doesn’t know the story from other sources) is similarly ignorant.

Sullivan doesn’t assert, but her book proves, that the NAACP saved America. Had it not been for the courage, resilience, inventiveness and general brilliance of the NAACP, America would have disintegrated, victim to the vicious racism of the American Southern white. The American Civil War (who knew?) ended not with a victory for the Union, but with a virtual Panmunjom-style truce, by which the South was allowed to pretty much ignore the 14th and 15th Amendments. The history of the treatment of black people in the American South after Reconstruction is about as ugly a story as you can find.

It’s true that the history of race relations in the North, by which I mostly mean racial discrimination against black people, is also not pretty. But in 1909, when the NAACP was founded, about 90% of all blacks lived in the South. And under the Jim Crow regime, the oppression of blacks by whites was complete. It was a terror regime, where lynching was an ever-present reality, and failure to abide by the most arbitrary and petty aspects of the code could result in ruination, battery, or death.

The NAACP was founded in the North but soon undertook to establish itself in the South. For decades–not years, but decades–merely belonging to the NAACP was a dangerous proposition, and assuming a leadership or organizational role could be an invitation to a hanging. And yet the NAACP did go into the South, and across the whole of the country, and they did devise a brilliant strategy that eventually brought Jim Crow to its knees.

What was this brilliant strategy? Well, I’ll only briefly summarize it because I want you to read the book. In a nutshell, it was (a) to mobilize public opinion, both black and white across the entire USA, to rally people of good will to a common purpose, and (b) to use the courts, including courts in the North and the US Supreme Court, but also, significantly, state courts in the Southern states, to acquire the rights afforded to all Americans under the 14th and 15th amendments, in particular the rights to vote and to a decent education.

But wait, you say. How could the NAACP use the courts to achieve their goals? Courts in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia? South Carolina??? The courts were white institutions, part and parcel of the entire white-supremacist establishment. The judges were racist, the juries were racist, the prosecutors and police were racist. It was virtually impossible for a black person to obtain justice under the law, and merely to seek justice in the courts was also to risk a beating or murder. And furthermore there were only a handful of black lawyers in the entire country, virtually none in the South, and very few white lawyers willing to take on black clients. So how did they do it? You’re going to have to read the book to find out. But you’ll be glad you did. It’s a breathtaking story, and expertly told by Sullivan.

Now let me tell you what I meant by my assertion that the NAACP saved America. With the First World War, the Great Migration of blacks out of the South began. And at the same time that blacks were moving out of the South, under Woodrow Wilson the federal government itself was institutionalizing segregation, making segregation not just the custom of the South but the rule of the land. The black migration out of the South increased during the Second World War.

After WWII, something had to give. Hundreds of thousands of black men had served in the war effort. There were lots and lots of soldiers, many of them combat veterans, who had done their all in a segregated Army to defeat the Nazis. And they were simply not going to put up with returning to living under the American apartheid system. In the North, the less overt but nearly as poisonous forms of institutional racism were starting to congeal. Had not the NAACP been there to channel the energies of post-war blacks and give them some hope of obtaining full citizenship at last, I can’t imagine — given the evidence Sullivan produces — that a race war would not have broken out in the American South. (Note: Sullivan does not say this. She nowhere says that the country was on the verge of falling apart. That is my interpretation of the facts as she presents them.)

To the great benefit of all of us, the NAACP was actively pressing an alternative to taking up arms to secure liberty for blacks in the South. But the NAACP was only *there* because it had established itself by patient work over forty years. By 1949 Thurgood Marshall was only one of a cadre of dozens of brilliant black lawyers working a relentless, multi-front legal attack on every aspect of Jim Crow — throughout the country, but especially in the South. By 1949, Thurgood Marshall already had 13 years of experience as a civil rights lawyer in many states and before the Supreme Court, and he had dozens of skilled black (and white) colleagues.

It was in this context that Rosa Parks’ bold gesture could spark a quiet revolution. Had she refused to give up her seat twenty years earlier she might have become just another lynching victim, but in any event we wouldn’t know her name. The NAACP had made the Montgomery Bus Boycott conceivable, and thus possible.

The NAACP was not a perfect organization, and its members were not all saints. There were rifts and factions and clashes of ego and long-standing feuds over strategy, tactics, organization, budget, and leadership. Sullivan lays them all out, buttressing her story with excerpts from letters, diaries, meeting minutes, memoirs, internal NAACP reports, congressional records, contemporary newspaper accounts, interviews and other primary sources. But whatever its flaws, whatever the foibles of its members, in the final reckoning, the NAACP prevailed. They made it possible for Dr. King to have a Dream. In so doing, they saved the nation. It’s an astounding story.

Lift Every Voice is a dense read, with hundreds of notes and several dozen important people to keep track of. But Patricia Sullivan’s voice is strong and the narrative propulsion is relentless. If you’re an American and want to know what country you live in, do yourself a favor and pick up this book today.