Text Copyright John Sundman 2008

Illustrations Copyright 2005 by Cheeseburger Brown

The smell of burning oak leaves greeted Mr. Norman Lux, nSF, as he slowly made his way down the hallways of the Old New Monastery towards the Courtroom of the Secret Chamberlains of the Cape and Sword, following a map made for him by the abbot himself, which he held in his trembling left hand. He walked uncertainly, with the aid of a simple cane, along corridors he had never seen before, through whole vast reaches he had not even imagined: past scriptoriums, cloisters, warming rooms and sleeping rooms, breweries, bakeries, cobbler shops, apothecaries, refectories, chapels, vestiaries and privies, all unused for centuries, empty, fallow, waiting since the troubles at the time of the last Painful Inquiry, in 1458.

Really he should have been using crutches, but it was important to him that he not look like he was overdoing it. This Painful Inquiry was a solemn office of the Church, and was to be treated with the utmost respect. The last thing Mr. Lux wanted was for the officers of the church to think he was doing anything for effect. According to his reading of the map he had only a few dozen more yards to go. And yet he did not know if he could make it the rest of the way unassisted, despite his best intentions. The nature of his Painful afflictions changed from day to day, but today he seemed to be suffering from leprosy, smallpox, and consumption. Every step was an act of will. He could scarcely find his breath. He prayed, “Dear Fred, please help me to arrive at thy Holy Door, but if not, thy will be done.”

His prayers were answered. He arrived at the entrance to the room where the Painful Inquiry was to be conducted, made the sign of the noose, and pushed on the towering doors. The doors swung open. With dread, terror and hope, Mr. Lux crossed the threshold. His Painful Inquiry had begun.

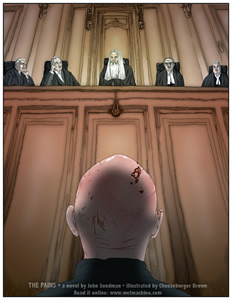

The room, illuminated by torches in high sconces and by a drop of drab sunlight filtered through a tiny roseate window on the right wall, was enormous, wood-paneled, and without ornamentation. There were a few wooden pews to the left and right, but the singular feature of the room was the high dais directly in front of Mr. Lux, a judicial bench at which sat five austere and angry-looking men, of whom Mr. Lux recognized only one: Fr. Hessberg, the abbot, who was in the center spot.

There was nobody else in the room.

Although Mr. Lux had requested this Inquiry, had dreamed of it for weeks and months, had read every bit of theological literature he could find on the subject (both sanctioned and unsanctioned), he did not know what to expect. He had no notion of how the investigation proceeded. And he felt terribly alone.

He walked to the center of the room, stood as erectly as he could manage, looked up to the men on the bench and said, “Norman Lux, a humble servant of Fred our Lord, stands before you.”

“Why are you here?” Fr. Hessberg bellowed, and his voice resounded off the cold stone walls. “We have assembled ecclesiastic authorities here at great inconvenience and great expense. What do expect us to do about your imagined worries?”

“Father,” Norman said, meekly. “I have been ill, and tortured, for so very long. Our doctors can find no cure, because the symptoms change from instant to instant. I burn up, I bleed from every orifice and pore, my bones break . . . I only hope to find some relief.”

“And you presume to diagnose yourself with The Pains?”

“Wise men, I am not learned enough to deduce such things. That is why I come before you.”

Wise men he said. But who were these men, he wondered. They were not even dressed in ecclesiastic vestments; rather, they appeared in the robes proper to a secular court.

“Well then tell us your story,” said a scowling judge to the abbot’s right. “Omit nothing, but do not embellish.”

As Mr. Lux tried to gather his thoughts, he noticed that the man on the far right side of the bench was crushing what appeared to be dry oak leaves into a bowl of some sort. He then proceeded to light them aflame using a taper that was in a tall candlestick. The leaves caught afire and the flame rose high. The man produced another bowl, and with a quick motion cupped it over the first to smother the flames. When he removed the covering bowl, the flames were gone and the leaves were smoldering. The man leaned his head over the bowl, breathed the smoke in deeply, then passed it to the judge who sat between him and the abbot. He too leaned over and inhaled the smoke, then passed the bowl further down. Mr. Lux stood in confused silence as each of the men breathed deeply the oaken smoke.

“You waste our time!” Father Hessberg thundered.

And so Mr. Lux told, as quickly as he could, in a dry, parched voice, the tale of his many weeks of suffering: the ailments, wounds and injuries, the fevers, agues, confusions. He told them briefly of his travels outside the monastery: his chaplaincy at Changes!, his coursework at the University of New Kent. But the men did not even appear to be listening; it was as if the smoke from the leaves had put them into a stupor.

“You say that you have been a chaplain at the prison,” a judge enquired. “You attempted to minister to a fallen novitiate from this very monastery. A dangerous man! Why did you take it upon yourself to attempt to redeem the Eagle?”

“Good sirs, I was following the orders of my abbot.”

The abbot said nothing. He appeared to be whittling a long stick, and his eyes were cast down. Why did he not confirm the truth of what Norman had just said? Mr. Lux had not known what to expect of this Inquiry, but he was surprised and troubled by the ferocity of his questioners. Maybe it was all an act, he told himself. Probably they had to be this severe to ensure that he was not play-acting. But could they not offer a hint of compassion?

“You have a theory about The Pains, is that correct? You think you know more than Holy Mother Church?”

“I come before you, to learn from you. I don’t presume —”

“Answer the question!” the abbot roared.

“Well,” Norman began, tentatively. He had not prepared a talk. He had jumbled thoughts, but no coherent theory. He knew he was going to embarrass himself, but he had no choice.

“Well,” Norman began, tentatively. He had not prepared a talk. He had jumbled thoughts, but no coherent theory. He knew he was going to embarrass himself, but he had no choice.

“I believe,” he said, “that The Pains have something to do with a soul about to go bad, a world about to go bad. But I believe that it is not a direct mapping, for the world is not deterministic. There is no cause and effect. It is chaotic, and only appears to be deterministic. Everything is information. Chaos percolates information from scale to scale, from microscopic to macroscopic, from macroscopic to galactic, from galactic to cosmic. This is the belief of the Santa Soga school.”

“School?” said one of the judges who had been silent until now. “School in Santa Soga? Is this not your school, St. Reinhold, your one true school?”

“Sir, I mean school of thought; a way of thinking about chaos. Like the Copenhagen School of Quantum mechanics. It has to do with unexpectedness. Surprise.”

“Surprise, surprise,” Mr. Lux heard one of the judges mutter.

The abbot spoke again, “No cause and effect, you say? Is all meaningless in your philosophy?”

Mr. Lux could feel his fever overwhelming him. Lights were pulsating, and the dais seemed to rise to the heavens. He tried once more to focus his thoughts.

“Karl Fritjof Sundman, the Finnish mathematician . . . Sundman’s three bodies —”

“What use is this information to us?” a Painful Inquisitor barked at him. “Chaos is what we reject, what we stand against!”

“Why have The Pains then descended upon you?” said another.

“That is a mystery of Fred,” Mr. Lux said. His voice was a mere whisper. “That is what I came here to find out.”

The voices became a tumult.

“Would you instruct us? You are the novitiate!”

“The story of Norman Lux, in other words, is the story of Frodo Baggins, Job, Fred, and every confused undergraduate struggling with Riemannian mathematics that he does not understand and for which he has neither the patience, intelligence, nor aptitude for hard work to understand.”

“Silence!” yelled the abbot, and the cacophony subsided. “The time has come to get to the heart of your heresy. Tell us about the machine you have made.”

With those words, Mr. Lux’s fever turned to chills. He did not know that they knew about his machine.

“I . . . I . . . I have been doing some experimental theology, reverend sirs,” he said. “I have made a machine for exploring chaos. An analog computer. To study strange attractors and fractal geometries of the soul.”

“Engine of the devil!” somebody said.

“The point of the church is not to enquire, it is to retard,” said somebody else.

“Where is it?” asked Fr. Hessberg.

“At the University,” Mr. Lux lied. And in those words he beheld his fate.

It was done. He had lied before Fred and his most holy representatives in a sacramental proceeding. For the first time, Mr. Lux came to believe that his Pains might never end. They might, in fact, merely be the foretaste of his own damnation.

“Whose soul is about to go bad?” the abbot enquired, staring right through Mr. Lux. “Is it your own, perhaps?” and then, calling towards the rear of the room, “Painful Witness, come forward.”

There were foosteps behind him; confident, military steps.

Mr. Lux turned and saw the soul gone bad. But what was the Party doing in an ecclesiastical matter? The Church, for all its faults, had always shunned the Party. This was, perhaps, its chiefest virtue.

“Carson Myers, Party Member in Good Standing,” the ruined soul said. “I am happy to help you with this ungood thinker. Religion requires freedom and freedom requires religion!”

Mr. Lux could feel the soul going bad, still, infinitely regressing, sliding away ever deeper into the labyrinthine world of doublethink. Knowing and not knowing, being conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, holding simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, using logic against logic, repudiating morality while laying claim to it, believing that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, forgetting whatever it was necessary to forget, then drawing it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly forgetting it again: and above all, applying the same process to the process itself . . .

Mr. Lux had come here today filled with the love of Fred, seeking only to do acts of peace and goodness, wanting only to discover why he was afflicted and how he might get relief. Clearly he now saw that that was not going to happen. There was no compassion to be found here today. The monastery, the Church itself, was banal, sterile, and cruel. Who were these inquisitors? They were dried up, politicking, senile old men. Why were there no women in this church? Only the virgins, the poor exploited girls.

“Where is this traitor’s infernal engine?” the abbot asked the jailor.

No matter how horrible Mr. Lux felt right now, at any instant he might feel immeasurably worse. Yet for all its superstitions and perversions, and for whatever reason of divine mischief or mere accident, the Church had stumbled upon some of magic; it had obtained some knowledge of The Pains that might be helpful to him, and which it was now withholding from him.

The Painful Inquiry had never been about the role of Fred in the world. It was merely about naked power wielded by a senescent, senile bunch of old farts whose time has passed them by. They were mere bullies. There was no need to show obeisance to them.

Fredianity itself was a fraud, Mr. Lux now saw, an institution of silly superstitions and pointless rituals based upon a childish myth. The Pains themselves were merely one part of that myth. Yet clearly he did indeed have The Pains. How could this be? How could he have this thing which should not exist? Had he brought them on himself merely by thinking on them? Were The Pains merely psychosomatic? True, he had meditated on nothing but The Pains for a long, long time. But if you meditate on the horns of a bull, to quote that old saint, you don’t grow horns. What then would he do for a cure? There was no answer. There was only chaos.

“It is a great and signal honor to perform my Freemerican duties by telling you that that machine is —”

But Carson’s voice was drowned out by the sound of a loud automobile engine with a broken muffler, spraying gravel, and rock music of some kind. Evidently a car had just driven to right outside the very Courtroom of the Secret Chamberlains.

Mommy’s little monster,

Mommy’s little monster

A violation. All things are coming together now . . . mysteries of faith . . . chaos theory tells us about infinite lengths in finite space, fractal dimensions, a bird in the water, a fish in the air . . . nonlinear dynamics . . . from this fusion The Pains were born . . . we see wars and desolations, depredations . . . financial meltdowns . . . melting glaciers . . .

Outside the door to the Courtroom, footsteps, people running. Voices. Xristi saying, “Where? Where?” Male voices saying, “Here, within!”

The doors flew open, and there stood Dr. Xristi Friedman, out of breath, holding a burlap sack in her right hand that appeared to contain something about the size and shape of a bowling ball. Blood seeped through it.

“It is her!” the abbot cried. “The Eagle’s muse! She has the knowledge! Seize her!”

Carson turned to chase her, and was immediately tackled by Mr. LaFont and Mr. Agnolli, whose black cassocks obscured his view as they sat upon him.

“Run, Norman!” they cried.

“Come with me,” Xristi said.

Run. Now that was a funny idea. And yet he must try. He looked up one final time at the stunned judges on the bench.

“All of your Fredianity has become mere sophistry! I am a soul redeemer!” he said.

He turned, and, taking Xristi’s outstretched hand, he left the room as quickly as he could manage. The doors swung shut behind him.

Mr. Chen and Mr. Powers threw their bodies against the doors, withdrew their cinctures and stoles from about their cassocks and used then to lash shut the giant handles.

“Run!” they said.

“I am melting,” Mr. Lux whimpered as he walked. The Pains were as bad as ever, but he had a new hope, now that he had abandoned the Church for good. “I need Sundman. Sundman, save me!”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.