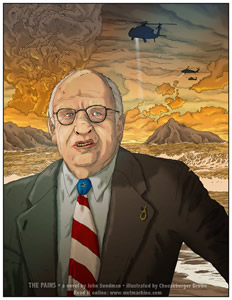

Text Copyright John Sundman 2008

Illustrations Copyright 2005 by Cheeseburger Brown

The Brain Institute of the University of New Kent was in some ways much as Xristi imagined the Monastery of St. Reinhold must be — full of empty rooms and hallways that echoed of past glory. It had been built before the Party’s ascendancy, with lofty goals of finding the causes of, and cures for, neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. But as the Party became more and more entrenched in society at large and at the University in particular, the practice of science necessarily became more and more corrupt. Science required logic and repeatable experiments, while the Party required doublethink and memory holes. Virtually no scientists remained.

Dr. Xristi Friedman trod quietly down the dusty and nearly empty halls of the sixth floor, past bulletin boards covered with faded flyers for programs from years ago, wondering if she could remember where Horatio’s office had been when he had a research fellowship here. The last time she had been here was a long time ago — before Horatio had quit school, joined the religious order, gone crazy, been sent to prison, and taken on the identity of a high-flying, all-seeing bird of prey. How innocent it all seemed now, how quaint. Horatio was an idealistic and handsome philosopher-scientist; Xristi was his randy scientist girlfriend. The search for truth was their shared passion, and the anti-truth menace that was the Party was a mere nuisance, a bunch of losers on the fringes of civil society.

When she saw the office door with the postcard of a Freemerican Silver Eagle perched atop a tree taped to it, she knew she was in the right place. She stopped before the door and glanced to her left and right: nobody. She inhaled deeply, placed her right hand on the handle, and turned. It was not locked. She pushed the door open and stepped into the little office.

It was a windowless room with a bookcase, a wooden roll-top desk with the top rolled down, a rolling chair and some pictures on the wall — one of her, before the tattoos, before the piercings. Yes, this was the place. It was in this very room that her lover had lost his mind.

She wondered if she were losing her mind too; the evidence clearly pointed in that direction. She was here looking for the Eagle’s apparatus, and if that wasn’t nuts, nothing was.

The apparatus was what the Eagle had been working on when the metaphysical thoughts finally overwhelmed him and he joined the Freduits. It was allegedly a mindreading device of some kind — built around the principle of the mindpixel — that could pluck a thought from the lively air, especially when placed close to the brain of a thinking person. Or so Horatio had said. But it was nonsense of course; Xristi knew that and had told him so. Metaphysics was not science, and Hebbian association–deformed surfaces of unit hyperspheres optimized for surface area were imaginary constructs, not real things that could be measured with a real device.

But ever since she had taken charge of the Chronos Collection, reality had become, for Xristi, a nebulous concept. It wasn’t merely that she had been told to do, and agreed to do, something that was stupid, impossible, and creepy. She had taken pride in being a scientist, but this wasn’t science. It was some kind of crackpot necromancy, magic, and cult voodoo. There wasn’t one chance in a million that any of the heads in her collectin would turn into anything other than smelly rotten meat when she thawed it. The entire Chronos Collection was a macabre and obscene desecration.

But all that, frankly, she could deal with. She wasn’t ashamed of her degraded position because she was being blackmailed. What alternative did she have? Had she refused, an innocent student would be locked up in Changes! So Xristi would do as she was told, even though she hadn’t the faintest idea where to begin. She would do her best.

No, the reason she was here today, the reason she feared she was losing her mind, was because of the one head unlike the others —the head of the sad-eyed young man with the rope burn around his neck. The head that seemed to be, impossibly, in a different position every time she went in the lab. The head that seemed to be trying to communicate with her.

For weeks now, every day she had gone into the Chronos Collection laboratory and placed blankets over the bell jar containing the head. And every day the blankets were on the floor when she came in the following day. Obviously anybody — Chancellor Meekman, for one — could have entered the lab when she was not there and tossed the blankets on the floor. But she couldn’t convince herself that it wasn’t the head itself that was rejecting them. The blankets seemed to muffle the weak communication — it wasn’t so much words as thoughts — emanating from the jar. But she could not shut them out altogether. It was absurd, of course. Her mind was playing tricks on her, tickling deep, deep superstitions from her childhood. But logic no longer mattered; she had to see if she could communicate with the thing.

She rolled back the desk cover, and there it was: a leather helmet like those worn by football players sixty years ago, covered all around with wires. Connected to the helmet by a length of string there was a little wand, sort of like a conductor’s baton.

“This is stupid,” she said. “Stupid, stupid, stupid.”

But she picked up the headgear anyway. She shook it and blew off a little bit of dust. Then, inhaling deeply, she placed it on her head.

It fit loosely, with two flaps on either side that rested lightly on her ears. She waved the wand towards the desk, the bookcase, the wall. And as she did so, she heard vibrato tunes at different pitches near each object, like the theremin playing in the Beach Boy’s “Good Vibrations”. But what was that? She heard words, faint at first, but growing louder, more distinct. And a kind of tapping at regular intervals. Oh! The tapping was somebody walking down the hall! Well, there would be no escaping; if they were coming for her they were going to find her. She raised the wand towards the door, and words, at first indistinct but gradually louder and clearer came in through the flaps.

oxide blue oven-dry Pan-mongolian New world palm marten monitor bug part-finished mid-forty nailhead spot mole-sighted mid-oestral mid-wall column oblong-elliptical moon-gazing pain racked peace overload circuit breaker mist-impelling needle dam mining claim mountain girdled oven-shaped needle spar new-risen occupation neurosis ocean-borne noddy tern milo maize olive acanthus nail maker Mid-victorianism nutmeg liver-footed or else parsley-flavored peace-breathing noncondensing engine own-form Nez perce ordnance sergeant olive family panel heating eagle office nurse crop Pan-slav passing bell movie-minded parliament man Pan-slavism mountain bunch grass neroli oil pale-dried pass boat nine-cornered paper birch niffy-naffy nimble-jointed nose-led mother cell otter sheep one-point paraffin paper neck-fast Non-bantu Mittel-europa motor assembler nail puller ox louse mulatto jack owl moth mockery-proof paper-capped night-robbing mis-strike oak-leaf cluster mowrah-seed oil oleander fern paramine brown open-jointed nanny plum onion smudge mis-seat mild-savored noun equivalent pad saddle paper chaser party liner

As the footsteps faded away and the words ceased, Xristi stood, amazed. Either this thing was rigged to play random words when a person walked nearby, or it was picking up some kind of emanation from the passer by and making it into words. Had the device been made by anybody other than Horatio, she would have dismissed it as a crude parlor trick. But she knew the Eagle, and he wasn’t the kind of person who would waste time with such things. So, just for the hell of it, she told herself, assume it it’s for real. What conclusions could she draw about the broadcast of seemingly random words she had just received? Well, it might be that the helmet could only pick up random words. Or, it might be that she had just listened to the actual thought, such as it was, of whatever person had just walked by. There wasn’t enough data to go on, and now the helmet was silent again.

But no, wait. There were words coming from someplace in the room. And in a voice that seemed familiar, friendly. Yes, that was it. She heard the voice of Minister of Awareness Ronald Reagan. Where was it coming from? A little experimentation with the wand quickly located the source: a folder on the desk. As she moved the wand over it, the voice looped back on itself, as if a dozen or more Reagans were talking at once. She took the helmet off, put it on the table, opened the file and read.

Memory does not correspond to any factual past, my friends. It only represents a current state of brain structures. It is more good to brainfix memories than to thingschange. See? Uncle Ron won’t steer you wrong! It’s a new morning in Freemerica! Brain science means more good control of ungood think and more findfix of ungood memories. Our brave men and women in uniform need more good tools to findfix ungood think. This is a matter of national security. He who controls the past controls the future. And remember, war is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength. Take it from me, Ronald Reagan. I’ll be keeping an eye on you.

Damn, Xristi thought. Is it possible that this apparatus really works? Fred Christ! Had the Eagle really been on the verge of building a mindreading machine? The Thought Police would kill for such a device. Why hadn’t the Party done something with it? Why was the helmet sitting here untouched? Probably because it wasn’t a mindreading machine, she realized. It was probably a gag.

Hang on. What if the Party didn’t know anything about it? What if only Templeton Cheney had known about it, and what if Templeton Cheney was dead?

There were too many mysteries. If she had had the time, and if she were not becoming increasingly paranoid, she would have blue-boxed some phreak buddies, arranged for some hackers to take it apart and see what made it tick. But there wasn’t time, and it was too dangerous. If this thing worked, she needed to use it. And she didn’t want anybody else to be caught with it.

In any event, she had been here too long and she was getting nervous. She put the helmet under her left arm, closed the desk cover, opened the office door, made sure that the coast was clear, and headed off at a trot. Ten minutes later she was manipulating the six large clasps that held closed the triple-insulated door to the Chronos Collection laboratory.

As soon as she got inside the laboratory she placed the helmet on the corner of workbench and, with a practiced move, picked the covers off the floor at the foot of the rope-burned man and covered the jar containing his pleading head.

Just moments ago, as she walked past the door to Chancellor Meekman’s office, trying to act nonchalant despite carrying a crazy leather mindreading helmet that she had stolen from her ex-lover and celebrated traitor’s office, she had been startled to feel the apparatus vibrate and squawk. Muffled voices percolated through it — Meekman’s, Reagan’s, and Oliver North’s, among countless others — saying mindless drivel in the Newspeak language of the Party. Amid the usual mixture of pseudo-patriotic blather, brain-numbing bureaucratese, and phony treacle, five phrases leapt out, loud and distinct: mindpixel, total information awareness, Xristi, Fred, Lux.

It was nonsense! It was bullshit! It would be comic if it were not so menacing. The Party was incoherent and absurd and couldn’t even tell her what it wanted her to do. But its guns were real, its soldiers were real, and its prisons were real.

Here she was, in a disused and Frankensteinian sub-zero laboratory. She had no idea what to do next. She had no friends, merely some people she chatted with on phone phreak bulletin boards. She had seen Norman Lux a few times since their first meeting, and although he was a friend of sorts, he wasn’t anybody she could really talk to — and besides, he was as odd as a seven-legged cat himself, and she needed a little normalcy for a change. Oddness she had to spare.

If you’re going to be alone, she thought, you couldn’t pick a better spot than this. Nobody ever came here because there was nothing to do here. The technology to reanimate these heads did not exist and never would.

Well, here she was. And there was the apparatus. If she was going to do the silly thing she meant to do, she might as well do it now, before the leather froze and became unworkable.

It was awkward to handle the helmet with her fat gloves on, but she decided against taking them off. The last thing she needed was to freeze her fingers so she couldn’t even open up the door to get out of here. Deliberately facing away from the blanket-covered jar, she steeled herself for the coldness she was about to experience, threw back the hood of her coat and placed the Eagle’s apparatus on her head.

Searing cold enveloped her, especially her ears. Cold air shot down her neck. Leaving the wand to dangle from the helmet’s left earflap, she pulled up the coat hood with both hands and pressed it tight to her head, willing it to warm up, which it did, slowly. And now she picked up the wand with her left, mittened, hand and walked around the room, deliberately avoiding the only head whose thoughts she actually expected to read.

She had never really inspected this place before. She had been in this locker dozens of times before now, but she had never stayed long. She had merely wanted to get a feel for what was in here. But without any research plan, without any ideas what to do with these gruesome artifacts, there wasn’t much point in exploring. And besides, although it was irrational, although it was unscientific, and stupid, she was convinced that the rope-burned head was that of Fred of Nazareth, and that it was trying to talk to her. Now, both because she was afraid to leave the room and because she was afraid to wave the wand near the rope-burned head, she decided to take a more deliberate inventory. After all, she was the curator.

The room was larger than she had realized. It was hard to know what shape it even was, so filled was it with pipes and tubing and valves and gauges and tanks and motors. And there was little light; the far recesses were dark and she had no idea where a light switch might be. She walked gingerly forward, with the wand before her. The helmet emitted not a sound, and with it on she could hear nothing, not even her own shuffling feet.

Eventually she came to a wall, in which there appeared to be a door — although it was hard to tell, because it was in shadows, and obscured by pipes and hardware. She leaned closer, and, squinting, made out some writing that appeared to say, “McKinley T.I.A.” She groped with her right hand until she found what appeared to be a handle, grasped it, and pulled, hard.

And came face to face with Monty Meekman, darkness visible. He was a giant, at least twenty feet tall, with the face of Ronald Reagan and Kron Borlak and Oliver North and the baby-faced man from the Two Minutes Hate. He was a wildly gesticulating man, and was also a dead, motionless rat that appeared to have a small weapon of some kind embedded between its bloody, broken ribs. His voice was soothing and avuncular, and he had an easy laugh. His voice was a scratchy rat’s scream that vomited out of his tiny rat’s teeth in his tiny rat’s head, which was locked motionless. He was an army, an air force; dozens of armies, child soldiers amputating limbs of other children, lobbyists for armament makers in congressional lobbies in McKinley DC; torture brigades and death squads and rapists, prison corporations, flag makers, propagandists, hate-makers, ten thousand nuclear-armed rockets in Freemerica and Korloon and Eastasia, fields strewn with mines through which children walked and were exploded, menace, threat, worldwide corporations beyond understanding or control, mafias, nihilism, fundamentalism, and love of power. The room itself was vast and tiny, galactic and infinitesmal, and pulsated one thought only: control. “I have always wanted to be here, to serve the Party,” the room said, Reagan said, the light-darkness said, the rat said.

“I have always wanted to serve the Party,” Xristi replied.

And then she was pulled back into the Chronos laboratory, flying through the air backwards, bent double with her fingertips touching her boots. The force with which she was ejected tore the Eagle’s apparatus off her head and it fell into the vortex. The McKinley T.I.A. door slammed shut. Still she flew backwards, seemingly for minutes. It was fun, actually, like being a child on a trampoline, playing with friends on a warm day in July in a serene and shaded back yard.

And then she was pulled back into the Chronos laboratory, flying through the air backwards, bent double with her fingertips touching her boots. The force with which she was ejected tore the Eagle’s apparatus off her head and it fell into the vortex. The McKinley T.I.A. door slammed shut. Still she flew backwards, seemingly for minutes. It was fun, actually, like being a child on a trampoline, playing with friends on a warm day in July in a serene and shaded back yard.

She landed, eventually, on a pile of blankets at the foot of the tank that was topped by rope-burned man. Slowly she got to her feet. With curiosity and gratitude, no longer with fear or dread, she looked into the eyes of the severed, tortured soul.

“Fer me ad lucem,” he whispered. “Bring me to the light.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.