Text Copyright John Sundman 2008

Illustrations Copyright 2005 by Cheeseburger Brown

On an architecturally bland stretch of Freedom Avenue in downtown New Kent City, Xristi Friedman stood leaning against a tree, smoking a Victory cigarette. It was ten minutes after six in the evening, and whoever was coming here to meet her was late. She glanced again at the handwritten note that she had found slipped under her office door two days ago:

Our mutual friend Horatio Norton, sometimes called the Eagle, suggested that I talk to you. Is there someplace public we might talk without attracting undue attention? Please respond with a personal prodvert in the Daily Exponent.

What kind of feeble cloak-and-dagger is this, she had wondered. A note slipped under a door? Reply by a notice in the personals section of a student newspaper? Yes, people who were afraid of the Party might not want to be seen on campus with a nonconformist like Xristi, but a note under her door was hardly secure, and a public reply in the student newspaper was unlikely to fool anybody. Nevertheless, Xristi’s curiosity had been aroused, and she had duly composed a response and delivered it to the Exponent’s office. The prodvert, addressed to nobody, gave the date, time, and location of the Grasshopper’s Pantaloons, the generic New Wave bar from whose interior the vacuous drone of Culture Club’s “Karma Chameleon” was now emanating.

The note’s elaborate yet oddly jangled penmanship made it look as if it had been written by a machine with a broken gear. Whoever had sent it to her claimed to have spoken with the Eagle, but that was unlikely. Horatio Norton was locked up in maximum security, and half-mad. Until yesterday nobody would have had any reason to make a connection between him and Xristi. Thank you, Colonel North, she thought.

But, she reminded herself, the telescreen emitted a neverending stream of ephemeral, self-contradictory bullshit. Its very purpose was to emit lies and ceaselessly contradict itself, and this story had probably been refuted already. So who knew what nonsense her tardy and mysterious correspondent might believe about her? Xristi was beginning to think that she had been stood up — that her Exponent prodvert had been too coy, or had not given sufficient advance notice — when a bus came to a stop a few yards down the road. Xristi tossed aside her Victory and looked up.

There emerged a young man in archaic clerical garb. It was an old-school get up, right down to the noose around his neck. He approached slowly, and appeared to be limping slightly. A leather bag was over one shoulder, and his hands were hidden in the folds of his garments.

God fucking damn Oliver North, she mumbled to herself. Just yesterday he had told the world that she was a Party member working to revive the frozen head of Fred Christ, and now here comes the Magic Christian looking for news of the revivification of Our Lord. She felt like turning and running. Ever since the disastrous end of her affair with Norton, she had a bad visceral reaction to men in cassocks. But something in the plaintive look of the friar or monk or pope or whatever he was, made her stay where she was.

“Are you, perchance, Dr. Friedman?” he said, looking about nervously.

“Yeah,” she said. “Who are you?”

It occurred to her that no matter who he said he was, he might be anybody. In particular, he might be a spy from the Party. She was suddenly angry with herself for having agreed to this charade.

“My name is Norman. Norman Lux,” he said.

He made a motion as if to offer his hand to her, but then he seemed to sense her reserve, and his hand stayed concealed.

“Shall we go inside?” he said.

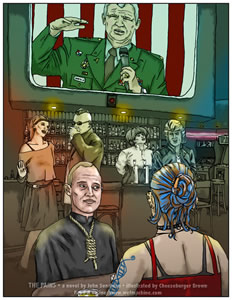

Xristi had chosen The Grasshopper’s Pantaloons because it had no personality and was less likely to be watched by the Party than the kind of punk places she favored. Inside were tables and chairs, a long bar, a few large telescreens and a smattering of generically hip proles. She and Norman Lux found a table and ordered beer from a waitress who seemed to appear as soon as they sat.

“You want to know about Fred’s head, I guess,” Xristi said. “It isn’t happening. It’s all a Party lie.”

“Excuse me?” Lux replied. “Head? Did you see my note? It was Mr. Norton —”

“The Eagle. Call him what everybody else does.”

“Yes. The Eagle. He said that you might be able to help me with a, how shall I say it, a personal matter —”

“And you’re not here to ask me about revivifying the head of Fred Christ?”

The man recoiled, looking befuddled. “I assure you,” he said. Evidently Xristi had guessed wrong. This young cleric was not here because of North’s pronouncement on the telescreen. And now he probably thought she was out of her mind.

“It is true that I am a novitiate in the Christian order of the Society of Fred,” he resumed, tentatively. “I reside at the Monastery of St. Reinhold. But my reason for wanting to speak with you does not have any direct relation to my vocation. As for the idea of revivifying the frozen head of our savior, I can only assume you are making some kind of macabre joke. The Eagle also speaks in such a way.”

“So what is this matter about which you would like to speak with me?” she said.

Already the Grasshopper’s Pantaloons was beginning to fill with young people of the new cubicle class recently released from their warrens. Behind Mr. Lux, above the bar, a giant telescreen was showing a football game; then the image changed to the Minister of National Well-being North. For better or worse, the telescreen’s sound was turned down and the cloying strains of Don Henley singing “Boys of Summer” supplanted Culture Club.

“It’s hard to know where to start,” the man began, and hesitated.

He was such an earnest fellow, Xristi thought. And so young! She felt a fleeting impulse that was almost maternal. On the other hand, perhaps her earlier intuition was right. Perhaps he was a Party plant, a spy. It would not be wise to trust him completely.

He continued, “Can you tell me about the research that the Eagle was conducting when . . . before . . . I mean . . . you know.”

“I’m afraid I don’t know,” she said.

Nearby somebody put some coins into an arcade video game, and the sounds of Pogo Joe’s startup music added to the growing din.

“What can you tell me about Templeton Cheney and the Eagle’s research into the nature of the mind?” Lux said. He seemed to spit out the words as if he were being prodded with a hot poker. Oh, so that’s his angle, Xristi thought. He didn’t want to know about brains, he wanted to know about minds.

Yeah, right.

She had to think how much to tell him. There was no need for her to mention the Chronos Collection. Not yet, anyway. First she had to learn a little more about this fellow. Was he really a monk? Did those people still exist? Did they go out to bars? The order had been on the very precipice of extinction when it swallowed her love.

“You reside at the monastery,” she said. “Yet you found my office on campus. You found your way to New Kent City to meet me here. For a hermit, you sure seem to get around a lot.”

The man nodded solemnly.

“I live in an uneasy truce with what we monastics call ‘the World.’ A few days each week I take classes at the university. Recently I’ve been called to be a chaplain at Changes! And I’m perfectly able to take a public bus into the city; one goes past St. Reinhold’s entrance. A monastery is not a prison, Dr. Friedman.”

“I know what a goddamn Monastery is,” she said.

Without a word, the waitress placed two glasses of beer before them. Then she stood there, seemingly transfixed by the odd couple, as if to join their conversation. Xristi gave her what she hoped was her most threatening look, and, after a few moments, the woman blended into the gathering crowd.

“You take classes at the university?” Xristi said.

“Indeed.”

“So, you’re a student. Of what?”

Xristi studied his face as Lux tried to respond. He seemed to have some facial tics; in fact, his whole face was twitching. No, it was more than that: his face was distorting in waves as he spoke.

“I’m a student of electrical engineering,” he said, finally, after what seemed to be a battle with his lips for control of his mouth. He leaned to open the leather bookbag that hung from the side of his chair. He took out a few academic journals and books and deposited them on the table.

Journal of Nonlinear Relations. Freemerican Mathematical Monthly. Stochastic Systems Review.

His hands were covered with peeling skin and scabs.

“Looks more like mathematics than engineering,” she said, studying the titles to avoid looking at him.

“I study digital circuit design, but lately I’ve become interested in nonlinear systems, analog computing. It’s a little off the beaten path. Most computers these days are digital, not analog.”

Much about this fellow was off the beaten path, she was coming to see.

“Why?” she asked. “What is it about analog computing that interests you?”

“I need to understand chaos,” he said. Again, he looked queasy, out of breath.

Xristi sat back and took a long pull on her drink. “You are a deep one, aren’t you?”

Lux didn’t answer. His skin seemed to be pulsing.

“Are you OK? Do you need air?” she asked.

“I’m afraid that my state oscillates rather wildly, unpredictably. I think I’m all right for now. Would you be willing to tell me of Horatio — the Eagle’s investigations?”

What the hell, Xristi thought, I might as well. After all, she realized, the Party could extort any information it wanted out of her as it had been doing, with implied threats of violence to Jane and Xristi’s other students.

“But just so I’m sure,” she said. “Will you confirm that you’re not here because of what Oliver North said on the telescreen last week?”

“I’m sorry. I don’t know who Oliver North is. Mercifully I don’t watch the telescreen; we have no electricity at the Monastery of St. Reinhold, where I reside.”

“Then I owe you an apology,” Xristi said.

“Not at all.”

“But what did you mean about the Eagle suggesting that you and I should talk? How did you even speak with him? He is locked up and not allowed to see visitors.”

“The Party does not allow him to see guests,” the man said. “But he is allowed to see a chaplain; in that capacity I met him. In fact, he explicitly requested a confessor.”

Ah, just so, Xristi thought. This was beginning to make a certain kind of perverse sense. Horatio and his metaphysics.

“And did he confess to you?” she asked. Did he tell you how he broke my heart and fucked me over?

“That is hard to say,” Lux said. “The Eagle speaks in riddles and odd locutions. I don’t really understand his meaning. If he has any meaning.”

“What did he say about me?”

“He said,” Lux began. Then, as he appeared to look for his words, his eyes opened wide, apparently in terror, as if he were looking at some horrifying monster standing behind her. His face grew contorted, he clasped both hands to his chest, and a loud yelp emanated from his mouth, even as his face became rapidly drained of all color, and covered with perspiration. Xristi was taken aback, startled. Before she could think how to respond, the waitress was there.

“He’s having a heart attack!” the waitress said. “I’ve seen this before.”

Xristi was having a hard time absorbing it all — the odd young holy man in anachronistic garb, the suspicious waitress materializing from nowhere, Oliver North mouthing his nonsense from the giant, soundless telescreen. She wanted to react, to say something, but felt immobilized.

“Somebody help this man!” the waitress called to an unhearing and indifferent crowd.

“Somebody help this man!” the waitress called to an unhearing and indifferent crowd.

“No,” Mr. Lux gasped, waving her off. “I’m all right. Really. I’m fine. It has passed.”

“Are you really all right?” Xristi said. “You look pale; she might be right, you might be having a heart attack.”

“No,” he said, somewhat forcefully, even as he panted. “I need to talk with you. And please have this spy leave us,” he added, waving his left hand limply towards the server. Xristi had looked away from his hands before, but now she could not avoid them. They were both covered with large lumps and scabs, from which there oozed what appeared to be pus and blood. Either she had not noticed how badly they were damaged, or they had gotten worse during the short time they had been together.

“Leave us!” Xristi barked. The woman retreated, and Xristi turned to Mr. Lux. Clearly, he attached great urgency to this meeting. He was suffering. Might he even be dying? She decided to trust him, to help him learn whatever he had come to learn from her.

“What did Horatio say?” she prompted, gently.

“I will try to remember his exact words,” Mr. Lux said. His voice was weak, barely audible over ’Til Tuesday on the jukebox Hush hush, keep it down now, voices carry . . . “‘You should talk to my friend Xristi Friedman. She deconstructs frozen brains for a living.’ And then later he said, ‘You shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free, Mr. Lux. Talk to Xristi. She can save you, although she could not save me.’”

From the telescreen, Oliver North appeared to be staring right at them; right at her. It’s only an illusion, she told herself.

“When did he say that?”

“Last week.”

“Where?”

“I saw him,” the man sighed, and winced, “In his change opportunity room, I mean to say prison cell, at the Changes! prison.”

“And he told you that I deconstruct frozen brains?” Xristi resumed.

“Yes. Are you not a professor of cryoneurology?”

“Only because that’s the title that Chancellor Meekman chose to bestow upon me,” she said. “I study low-temperature biology of the cell, including nerve cells. I don’t work with intact brains, even of the simplest organisms.”

“I see.”

What more did he want from her? But more to the point, why had the Eagle said that about her? Was it mere coincidence, or was her former lover Horatio Norton now perhaps collaborating with Monty Meekman? Had the Eagle been broken?

“Listen,” she said, “Father . . .”

“Call me Norman, please.”

“Norman. Listen. Long ago, when I was a child, I had an interest in life extension, in freezing brains to be brought back to life at some point in the far future. But I quickly learned that the freezing and thawing of brains is a subject for crackpots, not scientists. And the first time I had anything to do with ‘deconstructing frozen brains’ was last week, when Monty Meekman and the Party forced me to become curator of something they call the Chronos Collection, an obscene collection of severed heads. But I don’t see how the Eagle could know anything about that.”

She was leaning closer to him now, lowering her voice. He was listening, clearly trying to not grimace, but not succeeding.

A woman’s voice broke Xristi’s concentration. “How’s he doing?” The waitress asked.

“Get lost!” Xristi answered. Could this woman not take a hint?

“I don’t deconstruct frozen brains,” Xristi repeated, when the hovering presence had again withdrawn. “I do cell biology.”

“And you used to work with him?”

“When I met Horatio,” she said, “the Eagle, he was an idealistic young man interested in the so-called mind-body problem, the interface between the physical thing called the brain and the directly introspected experience we all have, that thing called the mind. He had obtained a fellowship at the university’s Brain Institute. He was brilliant and had a very mathematical mind, capable of thinking in deep abstractions. Eventually his deep thinking took a religious bent. He began to think obsessively, often going days without sleep. He took up praying. He became more distant, less interested in me, consumed with his theories of good and evil. He would spend days in the forests, alone, meditating, calling to the animals. Eventually he left science altogether and became a monk, like you.”

“And what about Templeton Cheney?”

“Oh him,” she said. “I never knew whether he was a real entity or a figment of the Eagle’s imagination. Horatio claimed that Cheney was his professor, his mentor at the Brain Institute, but no such name appeared on the faculty list.”

“You think Cheney’s a figment of his imagination?”

“Well,” Xristi said. “There was a laboratory rat, I was told, named Templeton — after the rat in Charlotte’s Web. The Eagle claimed that Templeton was an agent of the Party, working on a project called Mindpixel. Its purpose was to harness the Eagle’s theory in order to create an overmind, a giant network of some sort . . .”

“And did the Eagle, how shall I say this, did he . . .”

“Kill him?”

“Yes. Did he kill him?”

“That’s what he says. Sometimes. Of course, at other times he says he’s a mollusk or the Pope.”

“Precisely.”

“He’s nuts, you know,” she said. “Virtually everything that man says is nonsense.”

“His utterances do appear to be, how shall I say, chaotic.”

“Ah ha,” she said. “Chaotic.”

With that, neither of them spoke for a while. They stared at each other, not with hostility, but with a curious incomprehension, as when a dog stares at a child.

Mr. Lux spoke first. “So he may or may not have killed something or somebody that may have been either a person or a rat or a complete fabrication.”

As Mr. Lux was talking, the jukebox quieted, and the chatter in the room died down. People stopped playing darts and video games and turned their attention to the telescreen.

It took Xristi a moment to realize what was going on. “Two minutes hate,” she said.

“Right,” Mr. Lux answered. “Two minutes hate.”

The ritual might have been more appropriately called “two minutes mockery,” for the two minutes hate was more of a joke than real hatred. It was an ironic, self-aware ritual and everyone played along as if they were at a showing of Rocky Horror. A fat baby-faced man with a cigar was on telescreen, leading the cheers.

“Stupid hippies!” he called.

“Stupid hippies!” the bar patrons all answered together, laughing.

“Stupid feminazis!”

“Stupid feminazis!”

As usual, the face of Pete Seeger, the Enemy of the People, had flashed on to the screen, wearing a big smile as he played a banjo before a giant crowd of people dressed up like the mythical “hippies.” There were hisses here and there among the audience. Pete Seeger was the renegade and backslider who once, long ago (how long ago, nobody quite remembered), had been one of the leading figures of the Party, almost on a level with Big Brother himself, and then had engaged in counter-Freemerican activities, had been condemned to death, and had mysteriously escaped and disappeared.

“Pete Seeger is a Korloonian!” Baby-face yelled.

“Pete Seeger is a Korloonian!” Everybody yelled back.

“Stupid tree huggers!”

“Stupid tree huggers!”

The two minutes hate worked to a crescendo that ended with a boisterous singing of short chorus of Fred Bless Freemerica, and just like that, it was over.

“Fred, I hate that shit,” Xristi said. “I hate the Party.”

“Me too,” Mr Norman Lux answered. And again they looked deeply at each other.

As simply as that, they had become conspirators. It was tacit; there was no need for further comment. To say that you hated the Party was a crime punishable by death; they both knew that. And although the law was seldom, if ever, enforced, the implications were obvious.

Xristi said, “Why do you want to know about my work? What do you care about Templeton Cheney, frozen heads, all of this revolting nonsense?”

“Look at me,” he answered. “Look at me. I am dying.”

“You don’t look well,” she said. “And I’m sorry. You do look like you’re dying. But that doesn’t answer the question.”

Mr. Lux inhaled, and she could hear a wheezing.

“Tell me, did he ever mention something called The Pains?” Mr. Lux said, as he raised his beer glass and drank.

And as he sipped, Xristi noticed that the liquid in the glass was turning red. He placed the glass on the table, apparently unaware that there was something floating in it.

“Excuse me, Norman,” Xristi said. “But is that your finger floating in your beer?”

Mr. Lux peered down into the glass with a look of strained embarrassment.

“Oh dear,” he said. “Oh dear. I am so sorry to have dragged you into this. I apologize. Pardon me,” he added.

Then he reached into the glass, with his other hand, fetched out what appeared to be a finger, and rammed it back into place. “This happens,” he said. “I do apologize.”

“What the hell is going on?” Xristi said. “And where is that goddamned nosy waitress when you need her? Hey you!” she fairly screamed across the room. “Two more beers, right now!” And then again to Mr. Lux: “What is it? What?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I need to do more investigation.”

“Why?” she said. “You’re his chaplain. Something is not adding up. You went to great trouble to meet me. The Party could be watching us. Somebody from your own monastery could be watching you. Why? Why did you contact me? Do you hope that I’ll save you? I won’t save anybody. I only want to smoke pot, listen to punk music and do science! How will I save you, you poor man?”

“I have The Pains,” he said. “They will kill me unless I solve their mystery. You are part of it. And so is Horatio Norton, the Eagle.”

“Have you seen a doctor?”

“This is a spiritual condition,” he said.

“Oh bullshit. And who is that goon staring at us?”

“Where?”

“Over there by the Pogo Joe game . . . he saw me and ducked out the door . . . some dumb prole . . . I don’t like this place.” And then she added, “I hate the fucking Eagles.”

“Can you help me?” he said. “I don’t like this music either.”

“How can I help you?”

“I need to know about mindpixel.”

“Oh that,” she said, and felt tears welling up. “Oh, this is ridiculous!”

“How does mindpixel relate to your frozen heads, what do you call them —”

“The Chronos Collection.”

“— the Chronos Collection. How does this fit together Dr. Friedman? I am in extremis! I would not importune you otherwise!”

Around them in the Grasshopper’s Pantaloons, life went on as usual in Freemerica. The telescreen played above them, unremarked, the sound off. Ronald Reagan came on and said something presumably avuncular, Oliver North said something presumably militaristic. Clips were shown of military forces massing in far-off Korloon. Nobody in the place paid any mind; clearly their energies were directed to finding a coupling partner for the night. The speakers were playing “We Got the Beat” by the Go-Gos, very loud.

“I don’t know!” Xristi shouted at Mr. Lux over the growing din. “How could I know! For the love of Fred, your finger falls off in your beer and you just put it back in and go on as if nothing had happened? What in the world?”

“I don’t know either, Dr. Friedman,” Mr. Lux said. “I am barely half your age. I don’t want to die and I am nearly out of ideas.”

“Well I have an idea for you,” Xristi said, more harshly than she intended. “You know what I think? I think that the church and the Party are equally insane and irrelevant.”

She took a moment to try to compose herself. Some kind of something was going on; she needed to deal with it. It wasn’t this guy’s fault. He was merely caught up in it like she was.

“Tell me, Norman,” she said. “This Fred of yours. How did he die?”

“Well, he was hanged.”

“I know, I know, but tell me the story.”

“He was betrayed by Petrus, condemned by Pontius Pilate, hanged and decapitated, and on the fourth day he arose, with his head miraculously intact.”

“And you believe this shit,” she said.

But she was thinking: could it be? She had covered it up with shroud. She didn’t want to believe it was true that Fred was talking to her. But even now, as she sat in this bar, she could almost sense that head talking to her from its jar in Chronos.

“I am Fredian,” Mr. Lux answered.

“I have his head in my laboratory!” Xristi blurted out. “They want me to hook it up to their Total Information Awareness machine!”

“No!”

“You must go back into Changes!” Xristi said. “Find out what the Eagle knows.”

“It is too hard. There is too much pain.”

“You must,” she said.

“Mindpixel,” he said, grabbing her hand with his bloody paw. “What is it?”

She looked down at his gruesome hand on hers. She let it rest there.

“What is mindpixel? A theory of the transmission of consciousness through space and time? A new mathematics of the hypergeometry of thought? I don’t know what it is. It never made any sense to me. And it was so long ago. I have forgotten.”

Mr. Lux was clearly trying to compose himself as his body rebelled against him. He was drifting into absolute incoherence.

“My pains do no more than reflect the pains of the earth, the melting of the ice caps, the hole in the ozone layer, the despoilation of that which had been in ecological harmony since dawn of creation. Do you really think it is Fred’s head in your collection?”

“I do,” she said, admitting it to herself for the first time.

Thoughts swirled around in her cranium. What happens when you freeze a brain? Its cells explode. Brains frozen become nothing but mush. So how could it be that Fred’s head was speaking to her? And what could the Party want from her? The Party did not believe in science, of course. That was the paradox. How can you make progress based on scientific research when you do not believe in science because you must erase history?

“There is a legend,” the novitiate said. “An old folk tale. That at the exact moment that Fred’s head was severed from his body the sky opened up and a beam of impossibly cold light came down from the heavens, freezing the head and everything around it instantaneously. This is not orthodoxy, of course. This is heresy.”

“Well, I’m a heretic,” she said. “Big deal.”

“Most people are,” Mr. Lux said. “A true Fredian is a very old-fashioned thing, and quite rare.”

“But you are ridiculous,” she said. “How is your orthodoxy any less absurd than the legend of the frozen flashlight in the sky?”

“All I want to know is —”

“Stop!” Xristi said, urgently, motioning to him to shut up immediately. “Stand. Here, I will help you. Lean on me. We have to get out of here right now!”

She quickly pushed Mr. Lux’s various publications back into his leather bag and slung it over his shoulder. She stood, knocking the little table over as she did so. She grabbed his cassock; it slipped out of her hand and she found herself holding the noose around his neck and lifting him up by it.

“Come now,” she said, as a parent might say to a scared child in an earthquake. “Come with me.”

From several places at once, black-garbed and visored soldiers filled the room, weapons at their shoulders sweeping back and forth. Around the room people dropped their beer steins and raised their hands into the air.

“Loving greeting from Big Brother,” came a soothing masculine voice. “We come to assist all of you volunteers in filling out your applications to join the Peace Forces.”

“Come, come,” Xristi urged, and Mr. Lux limped on with her as quickly as he could, with his arm around her shoulder. Although there were soldiers at every door, Xristi had noticed that one place where the intruders had smashed through the windows was somehow unguarded. She led Mr. Lux through it, out into the night.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.