Text Copyright John Sundman 2008

Illustrations Copyright 2008 by Cheeseburger Brown

Mr. Norman Lux, nSF, as he shuttled down empty and seemingly endless corridors of the Monastery of Saint Reinhold, sometimes thought of himself as an electron following convoluted paths on a CMOS chip. In Saint Reinhold’s vast silent complexes of hallways, stairways, dormitories, infirmaries, courtyards, libraries, chapels, kitchens, classrooms, pantries, carpentry shops, lavatories, colonnades, iconic grottos, prayerful stations of the noose, and disused rooms of all description; in innumerable echoing vertices where he could choose to go upstairs or downstairs, left or right or straight ahead to get from point A to point B; at anonymous junctures where he chose which way to go based on whimsy and a general sense of his position and vector, without a map (for there was no map of the Monastery of Saint Reinhold: Who would have produced it? For whom to consult?)—in places he had never been before but which were somehow familiar to him—in his mind he compared his bounded explorations of the monastery to that of an electron scooting down a doped silicon pathway of a microprocessor, through AND and OR gates; through NANDs and NORs, doing its thing, performing its part in a computation infinitely beyond its subatomic comprehension. To the extent that any electron implemented a computer’s thinking, and to the extent that this very Monastery of Saint Reinhold was a consecrated place (Norman the Freduit novitiate mused), to that extent he himself was an aspect of Fred’s thought: Norman Lux’s trajectory itself, perhaps, even an infinitesimal computation of Fred’s divine mercy.

He wondered, Were his own movements through the maze really a stochastically dithered isomorph of subatomic pieces moving through some theoretical computer chip that was part of the same essential entity as Saint Reinhold’s: a self-similar tracing of a fractal pattern, an irresistible pull of Fred-only-knew what importance? But there he stopped himself. Such Tronish musings were mere mental masturbation of a short-pants theologian who also happened to be a part-time student of electrical engineering at the University of New Kent; a waste of precious time and an invitation to thoughts even more problematic. In particular, it was not good for Mr. Lux to think of the words “irresistible pull” and “masturbation.” His ordination, with its Vestal Tugs and the release of seven years of pent-up essence was still so far in the future as to be fantastical and hence an occasion of sin. He resolved to think of more wholesome things.

It had been three weeks since that painful morning when he had thought that he was going to die, when his bed had broken under a neutron star of a bedsheet. Three weeks since his odd interrogation by the abbot, which had culminated in a prophecy of a cosmic duel with Horatio Norton, the Eagle. During those three weeks Mr. Lux had concentrated on his studies—on the physics, not the metaphysics. He had tried to put out of his mind the notion that those inexplicable pains, that horrible suffering throughout his body that had made seconds seem like minutes and minutes seem like centuries, had been caused by a soul, somewhere, gone bad, or about to go bad. He prayed in the chapel, prayed while contemplating the body of Fred swaying gently in the breeze, while contemplating the mysteries of the noose, the stations of the rope—prayed that he would be able to put the idea of The Pains out of his mind. Largely he had succeeded. But not entirely. And now, today, he was going back to Changes!, back as chaplain. And he would minister to Horatio Norton, the former novitiate, the Eagle.

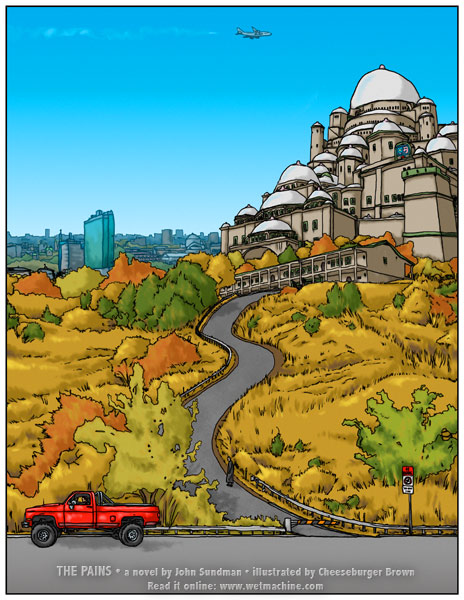

Cold bright sun assaulted Mr. Lux as he left the main arched doorway of Reinhold’s Gate, one of the seventeen major entrances to the monastery. He stepped into the sunlight, breathed deeply, and gazed upon the vast demesne of New Kent, seemingly at his feet. The monastery, which had once been a magnificence, a men-only city unto itself on a high solitary mount in a wilderness, was now embarrassed by its history and pretension. No longer a city unto itself, it was a gigantic building, empty, empty, empty, sustained on centuries-old canned goods and the kindness of strangers, perched like a pus-filled whitehead on the rude inflamed uprising that was Mount Reinhold, an archaic anomaly in a countryside long since domesticated, like a little vertical Sherwood Forest hemmed in on all sides by a relentless modernity. But still the view was breathtaking: fields, farms, roads, a university, a city . . .

Cold bright sun assaulted Mr. Lux as he left the main arched doorway of Reinhold’s Gate, one of the seventeen major entrances to the monastery. He stepped into the sunlight, breathed deeply, and gazed upon the vast demesne of New Kent, seemingly at his feet. The monastery, which had once been a magnificence, a men-only city unto itself on a high solitary mount in a wilderness, was now embarrassed by its history and pretension. No longer a city unto itself, it was a gigantic building, empty, empty, empty, sustained on centuries-old canned goods and the kindness of strangers, perched like a pus-filled whitehead on the rude inflamed uprising that was Mount Reinhold, an archaic anomaly in a countryside long since domesticated, like a little vertical Sherwood Forest hemmed in on all sides by a relentless modernity. But still the view was breathtaking: fields, farms, roads, a university, a city . . .

His black linen cassock quickly collected every joule offered by the sun, warming him against the chill as he began his long, steep stroll down to the roadway, down to the World. It was springtime, but closer to winter than summer. Another cold morning lay on New Kent, for 1985 was slow in warming. Mr Lux’s thighs complained at the strain of the sharp descent from Mount Reinhold, but Mr. Lux himself liked that the monastery was so archly perched. He liked the view of New Kent City and the surrounding countryside that the position afforded, but more importantly he liked that the place was hard to ascend to and no less hard to descend from. As a spiritual metaphor it was right. And Mr. Lux needed that rightness today more than ever. He did his best to absorb the metaphorical solidity of Fred’s mansion on a hill as he gathered himself to attempt a mission for which he felt totally unqualified and unprepared. Like a shy child in the wings about to go on stage for the first time in her life, stomach in knots, heart racing, dread in every cell, Norman would have given anything to delay this assignment. But already Mr. Lux could see Carson’s pickup truck—high on lifters, body polished cherry red, with chrome roll bars and oversized wheels—idling in wait for him. Carson Myers, Change Facilitator, was at the wheel a quarter of a mile away, waiting to give Mr. Lux a ride to the facility. Mr. Lux increased his pace. He had left the sanctuary; there was no point in dawdling. His legs began to ache in earnest.

Minutes later, having clambered up to its ridiculous height—tripping over his flowing black clerical garb like a lady in a Western movie caught in her petticoats mounting a stagecoach—Mr. Lux was buckled into the passenger seat of the four-by-four. Carson, a babyfaced and somewhat flabby big lummox of a man-child nearly twice the size of Norman Lux, sat in the driver’s seat, his creased Changes! uniform seemingly radiating the confident mission of the Ministry of Love. But Carson himself was morose today. Whereas on the few other occasions when the two had been together Carson had been voluble, a happy boy in a man’s body, today he had only grunted a hello as he put the vehicle into gear.

Mr. Lux hated this kind of situation: knowing he was expected to speak but having nothing to say. More precisely, he did have something to say, but what he had to say was silence. Here in the World, however, silence was incorrectly parsed as null and would not do. He was called upon to minister the word of Fred to a world sorely in need of it. After all, that was why he had left the cloistered maze of Saint Reinhold’s and gone out into the World today. The abbot’s injunction still rang in his ears: You must bear witness to Fred who was hanged in the noose! This is a responsibility you cannot avoid . . .

“You seem down today, Carson,” Mr. Lux ventured. “Is something bothering you?” He spoke meekly and blushed, aware of his outfit. As natural as the cassock seemed in the monastery halls, that was how unnatural it seemed in the World. He sensed blood rushing to his cheeks.

“It ain’t nothing,” Carson said. “Tiffany’s bitching about The Judge again and if there is one thing I cannot stand it is a woman bitching about a man’s pickup truck. Fred, that woman can be a bitch.”

“The Judge?”

“You’re sitting in him,” Carson said, patting the dashboard with his right hand and finally showing a small smile.

“And Tiffany being . . . ?” Mr. Lux asked hesitantly.

“My wife, Padre. My damn wife. I already told you that I’m sure.” The smile was gone.

Defeated on his opening gambit, he wished more fervently that he could say nothing. But Mr. Lux had started the conversation and now felt trapped in it.

“So you’re having troubles then? Many young couples need help learning . . .”

“We’re not having troubles, Father,” Carson interrupted. “She’s just bitchy. I still love her to death; she knows that. She’s cute as a pea in a pod. Her being a bitch comes from being knocked up; that’s the way they are. Those hormones get wrong and then watch out, squaw on the warpath.”

“Tiffany . . . she’s bound to be apprehensive with all the changes going on inside her and, um, all the new responsibilities looming ahead. Um . . . Be patient with her.”

“I’m plenty patient with her. Until she goes ragging on my truck right when I’m fixing to go to work dealing with some of the roughest change-needers in the whole theme park. She bitches about that too.”

“. . . about . . . ?”

“Tiffany thinks I should get another job.”

Carson was a simple man, nice enough, who loved his wife and his pickup truck; a prison guard who did not even know he was a prison guard but thought he was a change facilitator; a man who, like the Party itself, made no distinction between murderers, rapists, and people who had defied the Party by wearing a T-shirt that mocked Ronald Reagan—they were all merely people who needed to change. In Carson’s and the Party’s eyes, a maximum-security prison was a theme park where frowns could, with enough time and care, be turned upside down. Carson could not even comprehend the basic notion that Mr. Lux had not been ordained and thus should not be addressed as “Father.” What advice could Mr. Lux offer to such a man in such a circumstance? None. And yet he had been instructed by the abbot to go out into the World and minister the word of Fred. But in truth there was something else troubling Mr. Lux, and he was only giving Carson’s problems half of his attention. The other half went to the leather-covered tome that rested on his lap—the book he had been surreptitiously reading in his monastic cell for the last week when he was supposed to be studying circuit design. An ancient volume he had hunted down in one of Saint Reinhold’s obscure unused libraries, it was not exactly a forbidden book, but neither was it one he would want to be seen reading by the abbot. And it was certainly the kind of book that he did not wish to be seen reading by the person he was on his way to see. But absentmindedly he had taken with him this morning when leaving for Changes!, and he could not make it disappear. Nervously he lifted the cover and glanced at the gothic lettering on the first page:

He had no idea whether he would be allowed to take it into Changes!, yet leaving the book in the truck would be too complicated, and risky—Mr. Lux was not planning to go back with Carson today. Well, he would have to figure out something. In the meantime, Mr. Lux forced his attention back to his pastoral duties.

“Have you thought about that? Getting another job?”

“Well, Father, I don’t have to tell you that enforcing love is hard, dangerous work . . . Minister of Awareness Uncle Ron said so himself. And he personally handled plenty of tough guys. I know why Tiffany is scared. The Eagle himself is in Changes!. But if I don’t help him change, who will?”

“So you are a member of the Party, then, Carson?”

“Now you’re buttering me up, Father.”

That last remark left Mr. Lux truly speechless, and the rest of the ride to Changes! did take place in silence. Soon enough The Judge had been parked, Carson and Mr. Lux had passed through several different MiniLove checkpoints, had recited the proper loyalty codes—War is peace, ignorance is strength, Big Brother is the only Decider—and now the two men stood before the COR, change opportunity room, of Horatio Norton, the Eagle, himself.

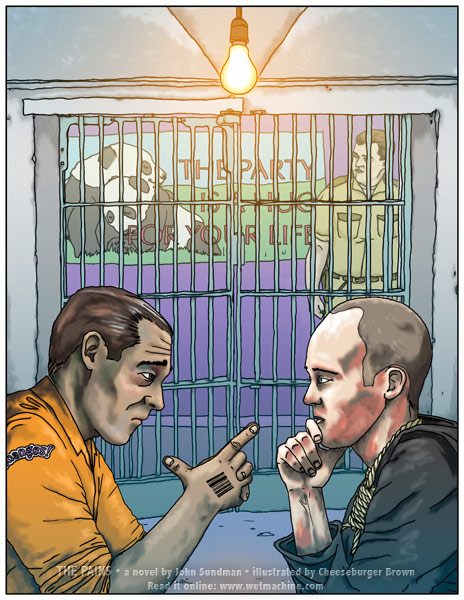

“Welcome to the panopticon,” Horatio Norton said. He was a handsome muscular man, perhaps forty years old, with an intense gaze. “How’s your pains?”

Father Abbot had said that the Eagle would challenge him, and already the challenging had begun.

“Good day to you. I understand that you have asked to see a chaplain?”

“You don’t have to go in there,” Carson said. “You can talk to him from here if you like.”

“Please open this cell and lock me in it,” Mr. Lux said to the guard and then, after that had been done, he took a seat at a small table opposite the Eagle said, “My name is Norman Lux. You may recall our having met. I’m a novitiate of the Society of Fred at the Monastery of Saint Reinhold, where I understand you yourself once studied . . .”

“What is the mind?” interrupted Norton.

“What is the mind?” interrupted Norton.

“Why are you here?” Mr. Lux answered.

“What is ‘here’? Do you mean why am I a guest at Changes!, or do you mean why am I a prisoner in this prison?”

“You tell me.”

“Bah,” the Eagle snarled. “I thought you might be somebody I could talk with, in English. But now I see you’re just a bullshit newspeak drone. Guard! Get this cretin out of my cell.”

“OK,” Mr. Lux conceded. “Why are you a prisoner in this prison?”

“Do you know what I am accused of?”

“No.”

“They say I murdered Templeton Cheney, the Party’s mannequin, and froze his little rat head in a meat locker.”

“Did you do that?”

The Eagle waved his bar-coded, tattooed hand dismissively.

“What is the mind?” he asked. “Have you any conception of that?” The Eagle was leaning intently towards him now.

“The mind,” Mr. Lux said as calmly as he could, “is that facility by which we can come to know the infinite goodness and mercy of Fred, and learn to love as He loved.”

“Do you know, why do they not kill me? Why do they not disappear me?”

“I don’t know,” said Mr. Lux. “Tell me.”

“They keep me alive for two reasons: they want to know what I know, and they want to change the way I think.”

“And what do you know that is so valuable to them?”

“What do I know? I know what mind is, and I know what consciousness is. Mind is a seven-dimensional hypersphere, and conscious thought is a great arc thereon, the shortest path between two points, two mindpixels.”

“Two points on a seven-dimensional hypersphere,” Mr. Lux repeated.

“Pixels of the mind. Precisely.”

“Why seven dimensions? Why not the four dimensions of space-time that you and I inhabit?”

“Ask God.”

“Did God engineer the mind, then?”

“Shut up and hear me. Optimal cognition is a geometric conception. Thoughts are trajectories on the Hebbian association–deformed surface of a unit hypersphere optimized for surface area. There exist evolutionarily plausible approximations of this mathematical object, and homologous structures to the theoretical object are anatomically and electrophysiologically identifiable in mammalian and nonmammalian species. This geometric conception of cognition, were it understood and embraced by smart people such as yourself, could serve to prime our expectations and plans for alien, artificial, and human cognition. Whether God made it that way or whether that’s the way it randomly evolved is not an interesting question to me. You should talk to my friend Xristi Friedman. She deconstructs frozen brains for a living.”

Mr. Norman Lux, nSF, waited a moment; waited to be sure that this expository speech had been concluded.

“And how about you, Horatio,” he said. “Do you want out? Do you want salvation? Redemption? Is that why you asked to see a chaplain?”

“Are you asking me if I want to change? Let me see your book,” the Eagle said.

“My book?” Mr. Lux was taken aback and his heart now leapt.

“Don’t be coy, young Freduit. The book under your outer clothing.”

Guardedly, Mr. Lux withdrew it from the inner folds of his black cassock, where he thought it had been well concealed. Not well enough, apparently. He placed it on the table and slowly slid it to the man opposite. Horatio Norton opened the cover and translated the Latin aloud:

“‘Notes concerning the Painful Inquiry convened by the grace of our lord Fred at the Monastery of Saint Hiram to investigate claims of chaos and affliction and impending world-end, as recorded by a true witness thereto, Damien Hessberg, year 1458.’”

“For my seminary studies,” Mr. Lux said.

“Liar!” the Eagle screamed, rising out of his chair. “You have The Pains!” Carson came running to the cell’s door, fiddling with his keys, but Mr. Lux signaled that all was OK. Carson stood back, dubiously, his hand on his billyclub. Horatio Norton sat and continued in a lower voice, staring right through Mr. Lux.

“Let me tell you something, young Mr. Lux. You are part of the corporate military-industrial-edutainment prison system, and your soul is more at risk than mine is.”

Mr. Lux was suddenly not feeling very well, and knew that he needed to make some progress if he was going to minister to this dangerous man.

“Did you kill and freeze the head of Templeton Cheney?” he said.

“The rat?”

“The Party mascot.”

When the Eagle next spoke it was as a different person. His whole face and posture changed, and he spoke with a gravelly voice and a thick Ebonic accent.

“I killed the motherfucker with a shiv I made in homeschool. It was a mordant bitch with a nice sharp point made out of pig iron. Sharpening the point was no big deal; you just drug it against concrete. This place full of concrete. It take time but here, time your friend. I wrapped the other end with upholstery and then some string and clay and dirt and shit and some, like, chewing gum, and some tape so that it made a handle. It was a righteous killing device. I’m homeschooled. I’ve been properly taught. Whereas some other denizen of this arrondissement might settle for a more pedestrian device, I specified pig iron on the manifest. That should give you some idea how I felt about this rat. Prison what in the mind. Pig iron for a pig. Here in B Block we call that justice. Where I got the pig iron, that’s the more interesting question. It came readymade in a box full of sawdust, that’s what.

“Sure I killed him. And why not? I didn’t like him. He was an arrogant fool. A cheerleader. A Texas oilman from Yale. I put that shiv so deep in his liver it came out his eyeball, and that blade was no longer than my dick. And he’s looking at me and saying, ‘I’m the Decider, I’m the Decider.’ Not now you ain’t. You dead. That’s what I decided. Here, the Schoolmaster say when you go in and when you go out.”

And then the Eagle added, in his normal voice, innocently, “Is that what you wanted me to say?”

“Who are you?” said Mr. Lux, as a headache began to sear his brain.

“You shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free, Mr. Lux. Talk to Xristi. She can save you, although she could not save me.”

“Only Fred can save either of us,” gasped Mr. Lux.

“Theology, that’s what I teach in my madrassa. And poetry.”

“Carson, if you please,” Mr. Lux said, staggering as he stood. “Please help me outside.”

As he fled down the hall, feeling hives erupting all over his skin and even down his throat, under his eyelids, he heard the Eagle calling out behind him.

“. . . It is for you the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which I have thus far so nobly advanced. It is for you to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before you—that from my bitchin’ shiv you take increased devotion to that cause for which I gave that cheerleader one last full measure of shit—that you here highly resolve that my upstroke shall not have been in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth . . .”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.