Illustrations Copyright 2005 by Cheeseburger Brown

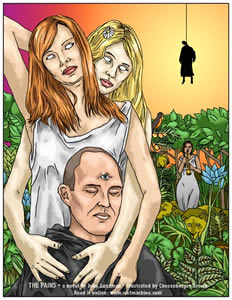

A buxom lass in the jungle playing a recorder. Her bosom heaves gently as she inhales, then gently blows. A blond woman, a dark haired woman. The word of Fred is pulsating, pulsating. It is warm here. Lux is safe. Who is this vision of beauty in diaphanous gown, whose breasts and slender arms, whose lips, whose, whose . . .

“Excuse me,” Lux tells her. “I seem to have lost my way.”

“Say what?” says the dark-haired one. Her light-haired companion laughs and cups her friend’s breast. Her teeth look menacing, but somehow oddly alluring. Her hand reaches inside his cassock. And a second hand, And a third, and a fourth, “Consider the lilies of the field” she says, “they spin not, neither do they toil.” Lux feels a life force welling up in him. They are tugging, pulling his love out of him.

They are tug-tug-tugging at the essence of his belief, the root of his being, as Fred was tugged by the rope. When the ultimate sacrifice is the purest bliss.

On that glorious, holy day, bosomy, gorgeous, teenage virgins dressed in lose-fitting billowy togas, with flowers in their hair, will approach the young men who are about to become priests. Beautiful buxom girls, virgins, beauties. Ample girls with round breasts, wide hips, full lips, nipples, hairy mounds, round asses — slender girls with upturned breasts and downturned smiles, narrow ankles and long fingers. The Vestal Virgins will slowly dance, slowly approach the waiting, nervous, seven-years-horny devotees of the Holy Noose. They will stand behind each in turn, rubbing up against each novitiate, their chaste breasts pressing gently against his back. And they will then reach into the flowing Freduit robes and . . .

Mr. Norman Lux, nSF, awoke, and ecstasy turned to familiar horror.

Mr. Norman Lux, nSF, awoke, and ecstasy turned to familiar horror.

These dreams of ordination day were becoming stronger and more frequent. Mr. Lux, in his days as a postulant before becoming a novitiate in the Society of Fred, heard little about the role of the Vestals in the sacred tug of the ordination. There were no recruiting brochures that spelled out how the ritual would unfold. It was not explained in his classes on the liturgy or dogma. And yet, and yet, the novitiates somehow learned, as if by osmosis . . . in dreams.

Long cold showers started his every day. Not only because he needed to cool his thoughts, but because once again he had ejaculated blood. His requests for clean bedclothes were no longer remarkable. The linen room had thousands of sets of white cotton sheets that had set on endless shelves for centuries; there was no need to conserve them.

After praying, bathing, praying, fixing his bed, praying and eating, it was time for Mr. Lux to go to Changes! He had lost track of the number of times that he had been there since the last time he had seen Horatio Norton. Each time there seemed to be a new reason why they could not meet, whether because the Eagle was meditating and refused to be interrupted, or because that wing of change opportunity rooms was being redecorated, or because there was a special theatrical performance that could not be interrupted. Mr. Lux did not know whether it was the Changes! staff or the Eagle himself who was canceling their meetings, and it really didn’t matter. Of all the places in New Kent, or even Freemerica, the inside of Changes! was the place where the concepts of truth and history had the least currency.

But still his pains grew worse. He prayed for relief, he prayed for understanding, he prayed that Father Abbot would at least entertain the possibility that Mr. Lux did indeed suffer from that rarest of theological afflictions, The Pains. His prayers were not yet answered (or not answered in ways that he could understand, he reminded himself), and so he directed his energies into his pursuit of chaos theory, blindly hoping for an insight that would lead him to freedom from suffering.

As he stood waiting for Carson at the foot of the hill, Mr. Lux was thinking about electrical engineering. At the University, in a hardly used corner of an obscure physics laboratory, he had found, amid old oscilloscopes and voltmeters and ammeters and logic analyzers, a Systron-Donner analog computer. And now he was trying to figure out an architecture for connecting that machine to the chip he had designed in his electric circuits class. He needed advice from somebody who knew much more about such things than he did, but there was nobody to ask. Under Chancellor Meekman, the professors who understood such things had been replaced by Party Members in Good Standing, who taught design from a Party-approved, faith-based pedagogy. Which meant that nothing they taught was falsifiable, and whatever they said one week might be contradicted by what they said the next.

If only he could get the Systron-Donner up here, to St. Reinhold’s, he could steal away in the quiet hours and pursue his research. Could Xristi bring it here for him, he wondered? How would he ask her? How would he dare? And then he would have to lug it from this spot up to the monastery himself; no cars went up that road. The place was still inviolate.

But what was he thinking? This was madness. Not only would it be a violation of countless of his vows, it was absurd! There was no electricity at the Monastery of St. Reinhold. But yet, but yet, something was going on, something must be investigated. He could not focus his thoughts.

Carson arrived and Mr. Lux climbed into the cab of his truck. Lux said hello, but Carson did not respond. Over the last weeks Carson had become less and less friendly, and Mr. Lux wondered why? Was it the stress of his job? His finances? Problems with his expectant wife Tiffany? Or, more likely, that Mr. Lux’s affliction was making him more and more revolting to look at, to listen to, even to smell?

Nevertheless, Mr. Lux was a minister of the Word. It was his duty to bring Fred into the hearts of all, and so he ventured, “And how is that lovely wife of yours?”

“You know what?” Carson said. “You’re a freeloader. This monastery should be paying taxes. You ain’t even real Fredians, walking around in your girly clothes. There is a war on. There’s a bunch of wars on. War on terrorism, war on drugs. And a war on them Korloonian sons of bitches is long overdue. So don’t talk to me, OK? And to answer your question,my wife is not acting right.”

They rode the rest of the way in silence.

At Changes!, to Mr. Lux’s dismay, the Eagle was ready to see him.

“Good day, Horatio,” Mr. Norman Lux said.

“It was a hot day in hogville when the long lost prodigal boy came back for a bacon sammich,” the Eagle said.

“What, I the prodigal?” Norman said, taking a seat. “I though it was you who was playing keep away.”

“When I walk down the streets of Colorado Springs, I am a happy man. Some Cheney might come up and fondle my member with never so much as a ‘by your leave’ and we can all construe that act to be a little forward, a little beyond generally accepted bounds of propriety.”

“Your riddles are tiresome, my ex-Freduit friend.”

“At the Air Force Academy things look more normalized. Things are in a row there. Fourteen airplanes by fourteen airplanes arranged like a chessboard as a surprise for the commandant. We have queer Christian preachers there too. For it is a grand, wide world.”

Mr. Lux knew that he should be ministering to this soul in jeopardy, but today he was finding it harder and harder to care about that. Weeks and weeks of wild goose chases, and now that he was finally here, this doubletalk. He found himself daydreaming about out how to program an analog computer to run the Atari game Pogo Joe. He forced himself to respond to the prisoner who sat opposite him.

“You say it is a wide world, but your world is very narrow.”

“At least there is electricity in my world.”

Well, now we are getting somewhere, thought Mr. Lux.

“I like it that St. Reinhold’s is without electricity,” he said. “I like the refuge.”

“It’s not entirely unwired, you know. When the house on the hill was ruled by Aldred the Apostate, the power was brought in.”

“I never heard of any such thing.”

“Of course not. Apostates are expunged from the record. Anyway, it was a failure. The mechanical-physical problems were insoluble, with solid floors and walls three feet thick. Besides, there was nobody who understood it, electricity. But there are rooms there, you know, where the electrons still flow, waiting for an outlet.”

“I think you’re lying. But come on, sir Eagle. You can see how I am. I don’t have much more time for this. Tell me what you want from me. Tell me what is going on.”

“Only you know why you have retreated from the world.”

Lux was becoming exasperated.

“You, sir! You had The Pains!” he was trying not to yell. “How did you escape them? And why are you really here, in this cell? What have you done?”

The Eagle’s expression did not change.

“There is a legend of the frozen lake. They say that when Fred’s body fell from the tree, the Sea of Galilee froze. Or something like that.”

“Must everything be a riddle? Have you no compassion?”

“Look to Sundman,” the Eagle said. “There is no riddle there.”

“And who, or what, is that?”

“He was a mathematician of Finland in the last century. He solved the three-body problem of astrophysics using new methods of numerical analysis. A great mathematician indeed. And an astronomer also, keeper of the Great Telescope of Helsinki.”

“Why are you toying with me? To communicate with Xristi? To communicate with the Abbot? Why did you call me here?” Mr. Lux felt tears welling in his eyes. He wiped them, and his fingers felt sticky. He knew it was blood. “Your soul is about to go bad, and with it the world. Innocents suffering by the millions.”

“Not my soul, young sir. And the suffering of innocents is something for you to take up with your God, or at least your Abbot. If he’s not too busy passing secrets to Korloon. Or to Big Brother.”

“I will not sit here and listen to you slander Father Abbot! Damn you, man. You know I have The Pains and you know your soul is about to go bad. Will you not free me of this torment?”

“You blaspheme now. It is God’s grace alone that can free you. Or his sacraments, an old battle that doesn’t concern me in the least. In any event, your Pains don’t concern me. If you want relief, I suggest you speak with yon big dumb bag of meat.”

“Fred have mercy,” Mr. Lux muttered.

“The three-body problem is the last solvable instance of the N-body problem, by the way. There is no solution to the four body problem or the five body problem. And yet there are an infinite number of bodies that interact, are there not? Sundman’s three-body solution is one of the first precursors to chaos theory; it’s an example of a deterministic problem that quickly becomes intractable and appears to behave chaotically. So our Finnish friend not only did important work in the 3-body version, but he anticipated the machines necessary to attack such problems in general.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Sundman was really the last gasp of the old deterministic worldview, basculating on the threshold of chaos.”

“So,” Lux said. “I see. You are telling me of the mathematics I need. Does it relate to your mindpixels and seven-dimensional hypercubes of thought?”

“I am not concerned with three bodies in space, but with three consciousnesses in three bodies. This is what is called theology. Or Reaganomics, if you will.”

“Damn you! Tell me what you mean!”

“Those pains ordained by dark chaos! Those pains unreasoned: murder, child neglect, dwarfism, a black woman in spiked heels forever excluded, that poor woman in a window, kidnapped, trafficked.”

“Who is she?”

“A sex slave. This is the coupon of endless war. A traffic in women and children; strife, hatred, lovers drowning in inland seas.”

Carson, who was still standing outside the cell door, now spoke, with a laugh.

“Well, he’s talking nonstop bullshit as usual, but I would know what to do with that woman in the window wearing high heels.”

“Carson, if you please. I am here as a chaplain. I must be allowed to converse without your listening.” Mr. Lux was beginning to actively dislike the man.

“I must say that that’s a violation of basic decorum as far as I’m concerned,” the Eagle said. “But there is no such thing as a conversation that is not overheard. Not outside of your priestly mansion.”

Mr. Lux was feeling more ill by the moment, with countless ailments and injuries that he no longer even separately noted. He knew that he needed to conclude this interview soon.

“I think that is overblown,” Mr. Lux said. “Most telescreens don’t even work.”

“In Mckinley DC, there is a project of the Freemerican Security Agency called Total Information Awareness. Templeton Cheney is in charge of it.”

“I thought he was dead?”

“You vex me, child. I say he is dead but he is not dead. I speak of his simulacrum, the Party, the flesh made word.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Lux. “I understand. Cheney is the embodiment of the Party.”

“He is in his own frozen head.”

“And where is this frozen head?”

“In the time-teleport connection between New Kent and McKinley. The only science being seriously pursued is that which leads to authority and control.”

Ever more nonsense and riddles, and Mr. Lux’s fever was melting him.

“Tell me about frozen heads. What made you say that Xristi deconstructed them? She does no such thing.”

“Perhaps she doesn’t yet. But she will. Where is my absolution?”

“There is no absolution without repentance, and you have not even admitted sin. Besides, I’m no priest, as you well know.”

“You’re an elementary particle carrying charge.”

Mr. Lux could take no more. “Carson,” he said. “Please let me out of here. Mr. Norton, I wish you well. We will not be meeting again.”

“We shall meet with our minds beaming across the universe, reconstituted in a neutron star.”

“I will let you out, but I ain’t going to take you home, Padre,” Carson said. “I’m through with that.”

“Aldred the Apostate,” the Eagle said. “Oldest of the new.”

“You’re on your own,” Carson added.

That was just as well, as far as Mr. Lux was concerned. He didn’t want to go back to St. Reinhold’s just yet. The walk from Changes! to the University was not far, and he knew where Xristi’s office was.

Several hours later that night, after having missed dinner and evening prayers, Mr. Lux got out of the passenger seat of Xristi Friedman’s battered Volvo at the foot of the road to St. Reinhold’s. With her help, he lifted the tailgate. Inside was an old, hacked, Systron-Donner analog computer strapped to a purloined hand truck. They removed it from the car (where it had been wedged in among canisters of liquid nitrogen) and set it gingerly on the ground. Refusing again her offer of further assistance, Mr. Lux began to slowly make his way up the gravel road, dragging the hand truck behind him, inch by tortured inch.

The Volvo sped away.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.