Text Copyright John Sundman 2008

Illustrations Copyright 2008 by Cheeseburger Brown

Professor Xristi Friedman, Ph.D., dressed in blue jeans and a flannel shirt—the most conventional outfit in her possession—stood, arms akimbo, before a chalkboard at the front of the amphitheatric classroom and surveyed the chittering, chirruping mass of University of New Kent students settling into her lecture class, “Anatomy 304: Selected Topics in Low-Temperature Biology.” Behind her, twin telescreens on either side of the chalkboard were playing Happy Celebrity Gossip with Regis and Mindy at a moderate volume; its blathering hosts, perched on stools, their faces stretched in the vapid rictus of the newstainment presenter, were, as always—while prodverts streamed above and below them—pretending to have a conversation about some phony topic of no consequence. Even with her back to Regis and Mindy, Xristi could not avoid seeing them, for along the drab concrete walls on either side of the hall there were two more telescreens beaming obliquely back at her. Near one of the telescreens, she noticed, there was fissure—a half-inch wide crack that had appeared after the most recent earthquake last week.

The bell that signaled the start of classes had sounded more than two minutes ago, but students still straggled in, chatting, laughing; careless that they were late and disruptive. Although Xristi had toked up before leaving the parking lot and now had a mild buzz on, she was nevertheless irritated by her students’ habitual rudeness. These kids are assholes, Xristi thought. Why do I care about teaching them?

It had been three weeks since she had received the letter from Chancellor Montgomery Meekman directing her to stop teaching her classes, discontinue her research on the cryobiology of small amphibians, and take up stewardship of the macabre assortment of frozen human heads known as the Chronos Collection. During this interval Xristi had tried to act as if she had never seen the chancellor’s letter. She had neither responded to it nor mentioned it to the chairman of her department. She had continued to teach her classes, supervise student laboratory sessions, and conduct her own research on frogs and tadpoles: freezing them in liquid nitrogen, thawing them at different rates and in different solutions, and meticulously documenting what happened to their cellular structure, particularly their nerve cells—particularly their little amphibian brains. She was happy that she had not cowered in the face of Monty’s threat, not surrendered at the first shot; she felt some small measure of pride that she had not allowed the Party to bribe or bully her into abandoning her passion with a simple “promotion” to the Chronos curatorship.

But nevertheless, she ruefully admitted to herself, the letter had, indeed, affected her. Without having made a conscious decision to do so, over the last three weeks she had cut down on the Party-bashing in her lectures; she had said “fuck you” to the telescreen in public places less frequently than she had before. On one occasion, she now blushed to remember, she had avoided a small antiwar demonstration that she normally would have joined. Heck, she had even toned down her wardrobe, gone a little conservative—although her hair was still blue, her arm was still tattooed up to her shoulder, and her ears still jingled with earrings and safety pins. But the point was, the letter had rattled her, caused her to change her behavior, to act out of fear. Xristi knew that the Party was not as all-powerful as it pretended to be, but that wasn’t the point. Its power, while not absolute, was real. She could not ignore Meekman’s letter forever; at some point a reckoning would come. If she did not reach an accommodation with the Party she would, sooner or later, lose her appointment to the university faculty, and with it her contact with students.

And of course if she lost her faculty appointment she would lose her laboratory also. And that would be the end of her scientific career. Which would be, effectively, the end of her. For Xristi Friedman had no love life, no real friends, no hobbies other than smoking dope and listening to punk rock; no pets, no money, no secret longing to travel to Portugal, Paraguay, or anywhere else. Once she had had a lover, a soulmate, someone who knew and completed her every desire. But he had gone mad and now he was locked away, and that was that. All she had left was her science. And of course the Party knew all these things about her, and more.

The Party was playing hardball, and Meekman’s letter was clearly a threat: Stop teaching, give up your laboratory, and take over the Chronos Collection. Or else. But Xristi had something the Party wanted, and to get it the Party would cut a deal; she was certain of it. The Party was nothing if not cynically pragmatic. But how hard could Xristi push? That was the question. Obviously the Party needed her for the Chronos job—why else would they have offered it to her, Xristi Friedman, a Democrat who mocked the Party with every breath? The Party wanted her to stop teaching; that much was pretty clear, and it wanted her to do something—exactly what was not yet clear—with the Chronos Collection of frozen heads. But, Xristi reasoned, the Party didn’t really care about science, so presumably it wouldn’t care if she continued her research on slimy amphibians. There was room for compromise.

All she had to do was leave this classroom, now: walk down to the chancellor’s office and tell Monty Meekman, “I’ll stop teaching and I’ll do whatever you want me to do with the stupid fucking frozen heads, but I get to keep my lab.” She would have a deal in a McKinley minute. But what if she, like Socrates long before her, refused to stop teaching? What then? And abdicating her role as a teacher was proving more difficult than she would have imagined.

So why was it important to her to keep teaching undergraduates? Ninety-five percent of these of these kids were either empty-headed proles or Party-Members-in-training. They didn’t respect her; that was clear but it also didn’t matter. What mattered was that they didn’t respect the subject matter either. In fact, she had no idea why they even bothered to show up for class, so shallow was their interest. So what was *she* doing here?

Xristi glanced at her sheet of handwritten notes for her lecture today. The subject: “On techniques of replacing water with substances that cause less cell damage during freezing and thawing.” A formal title and a simple bulleted list to remind her of what she planned to say:

- Sugars and other solutes that do not easily crystallize have the effect of limiting the stresses that damage cell membranes.

- Trehalose is a sugar that does not readily crystallize and is thus cryogenically interesting.

- Mixtures of solutes can achieve similar effects.

The answer to the question of why she still taught, she realized, was one word: Jane. Jane was the last student she cared about. Over the past three weeks, all other serious students had stopped coming to Xristi’s lectures. Auntun, Paula, Hollingsworth, Barlow, Ande: all AWOL. Of the core group of students Xristi had identified as real potential scientists, only Jane—shy Jane, studious Jane, solitary Jane, Jane who sat in the front row with her notebook open, pencil at the ready—remained. What had happened to the others? Why had the best, most motivated students stopped coming to class, while all the dunces still filled up the lecture hall three days each week? Who knew? But as long as Jane showed up for class, her professor would too.

Xristi mentally rehearsed her opening comments. As soon as these last few stragglers, Party Youth members in Oliver North T-shirts with Freemerican flag motifs, found their places . . . She glanced at the ceiling cameras tracking her, discretely flipped them the bird, walked to the lectern, pressed a button.

On the screen behind her, an image of a microscopic organism appeared.

“What can microscopic life tell us about macroscopic life at low temperatures?” Xristi began, talking over the din. “Water bears—” she pointed over her shoulder at the image behind her, “you can call them by the fancy name tardigrada—tiny multicellular organisms, can survive freezing at low temperatures by replacing most of their internal water with the sugar trehalose. OK, that’s a clue. But mammalian cells are not microbes, and it turns out that replacing water in mammalian cells with trehalose doesn’t work. OK, trehalose is out, but what about some other solute?”

Xristi, aware that she was rushing her talk, looked out on a field of blank stares, snickers, and one lone hand raised.

“Jane?”

“Salts?”

“Good. But some solutes, including salts, have the disadvantage that they may be toxic at high concentrations. Remember, two conditions usually are required to allow vitrification—an increase in the viscosity, and a depression of the freezing temperature. Many solutes do both, but larger molecules generally have larger effect, particularly on viscosity. Rapid cooling also promotes vitrification . . .”

Damn, maybe Xristi had gotten more stoned than she had intended. On the telescreen, Oliver North had replaced Regis and Mindy and was droning on at low volume against a backdrop of Freemerican flags. As if drawn by an ineluctable force, student faces turned to him, like flowers to the sun. He was chatting with an obese bald interlocutor, a well-known Party fluffer known as The Voice.

“Can you imagine if Fred Christ Himself were to be thawed and revived?” the bald Voice asked his audience as North nodded sagaciously. “Well, my friends, research to hasten that very outcome is underway at some of the Party’s preeminent laboratories even as we speak. According to my sources, Professor Xristi Friedman, a Freemerican scientist, Party Member and research scientist at the University of New Kent is developing techniques that will make this dream a reality, and soon.”

“The implications for our way of life are staggering,” Colonel North said.

So that was why her class was so full. Behold the power of the telescreen to shape reality.

“Hey!” Xristi called out. “Forget that jackass on the telescreen for just a moment. Hey!”

While most students kept their attention on the telescreens on the left and right walls of the hall, about a third of the students seemed to be looking at her—although some of them were probably looking past her to the telescreens at her back.

“If you believe what he’s saying about me, you’re even stupider than I thought. Please give me your attention and answer one question for me. How many of you here today are in this class because you want to learn how to live forever?”

That question, at least, got their attention. Students looked at each other. Hands went up, sheepishly, then proudly. Soon most of the class had their right hands raised. The drone of low-volume conversation on the telescreen permeated the lecture hall.

“Meanwhile the terrorist regime in Korloon is not sitting still,” North was saying.

Out of the corner of her eye, Xristi saw something to her left. She glanced over to see Monty Meekman was looking in through the narrow vertical window in the classroom door. Great. Well, let him look.

“Listen, you fuckbrains,” Xristi said to the class. “This is a cryobiology class. Low-temperature biology. Cryobiology is not cryonics. Cryonics is the pseudo-science of freezing brains to bring them back in the future, and we’re not going to get into that subject in this class for the simple reason that it’s pure bullshit. And furthermore, I do not work for the Party, and I do not have any access to the frozen head of Fred Christ, for Christ’s sake. Do you think they had vats of frozen nitrogen sitting around to freeze dry him after his noosifiction? What baloney!”

“That’s not what Chancellor Meekman says,” called an insolent voice. Xristi scanned the hall until she found its source. Of course. The Oliver North T-shirt kid, the one who had been last to enter the hall. “That’s not what The Voice says.”

“Oh?” Xristi said. “What does Comrade Voice say?”

“The Voice has said that big things will soon becoming out of university labs. A glorious future for the Party. And immortality for all those who accept the Party as their person savior.”

“Fred fuck,” Xristi muttered. She was swimming in a sea of insanity.

“You have an obligation to bring on the transhuman future, the Overmind, the Rapture,” said the Party Youth member.

“Obligation to whom?” She was getting angry now.

“Obligation to Christ, to the Party.”

vThat’s not true. This is a university,” she said, though she knew it was futile. “You are in a science class at a university. The function of a university is to increase our store of knowledge. Science is methodology for finding truth, and my only obligation is to the truth!”

“Do you deny, then,” said another student, “that Freemerica is a Christian nation?”

From the speakers behind her, Xristi heard Minister of National Well-Being Oliver North saying something about Korloon. The Voice interrupted him.

“We know for a fact that Kron Borlack has been supplied with dangerous secret information. Weapons-of-mass-destruction secrets. The Freemerican government has learned that Kron Borlack recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa. Friends, this is not child’s play we’re talking about. This is mushroom-cloud stuff . . .”

“Rumsfeld sold weapons to Korloon!” Xristi yelled at the class. “Reagan is in bed with Kron Borlack still! This is all a plan to make you afraid. Have you no memory?”

“You should watch what you say,” said a pretty blond girl in the front row five seats to the left of Jane. “Big Brother is watching.”

“Big Brother,” said a pretty brunette girl in the seat next to her, “is striving day and night to keep you safe. You should show a little respect.”

The Texas Twins, Xristi called them. You could always count on them for the Party line, the menacing hint.

Meanwhile Oliver North intoned:

“. . . that liberal hero known as the Eagle gave Korloon every last bit of know-how they needed to wipe the greatest nation known to mankind off the face of the earth!”

Involuntarily, at the mention of the Eagle, Xristi turned to the telescreen behind her to her right side. It was showing a picture of a young Horatio Norton, looking like a Sampson from an earlier era, his long hair blowing in the wind as he gazed into the distance, arm in arm with a beautiful hippie-ish girl . . .

“Oh, this shit has got to stop!” Xristi said. “How can I teach you anything with this nonsense blaring?”

With three quick strides she was at the wall. She reached behind the telescren, grabbed a handful of wires, and pulled. Who are you? Where did you go? Xristi silently asked the image of her impossibly younger, impossibly more innocent self, as the screen went black. Somehow, miraculously, all four telescreens went dark and quiet.

Xristi turned and looked up to a lecture hall filled with stunned and silent students. There was not a sound anywhere.

“Much better,” she said. “Now let’s talk about the physiology of the human brain. The fact that tissues can be revived does not mean that people can be revived. It’s true that we can preserve sperm or embryos in liquid nitrogen. But not brains. It is the cells’ thawing that is the problem, not their bursting. When cells die, autolysis—self-eating—begins. That goes on whenever cells die. As soon as you thaw a brain, lysosomes come out of their membranes and eat whatever they can find. And that explains, children, why human brains cannot be frozen then thawed. Even before the microbes come to eat your cells, the cells have eaten themselves. I’m not going to waste my time with point-by-point refutation of intelligent resurrection theories of Party goons, theocrats, and transhumanist nutjobs. But if intelligent resurrection is your reason for being here, kindly leave. I’ll give you all passing grades, so no worries on that score. But here is simple fact: You are going to die. Everybody dies. The Party is not going to save you, and neither is Fred Christ. So take your books your Party Youth badges, and your Freemerican flag noosifixes and get out of here.”

But no one made a move to leave. Whether they were terrified by the crazy woman at the front of the hall, or merely still in shock from the absence of the telescreen was impossible to say.

“You, Jane,” Xristi said, addressing her. “Why are you in this class? Are you too looking for the key to your salvation? Are you here for the Rapture?”

Jane blushed, hesitated, then said in a voice that was nearly a whisper, “I just want to understand biology. Maybe learn something medically useful . . .”

Before Jane could complete her thought, all four doors to the lecture hall, two at the front and two at the back, swung open, and black-garbed soldiers wearing body armor and visored helmets filled the hall, assault rifles at their shoulders sweeping rapidly left and right. Screams filled the air, but students kept in their seats.

“Well, that was quick,” Xristi said. It had been less than a minute since she had disconnected the telescreen. Or maybe they had been dispatched when she gave the screen the finger? Who could tell? “Now I guess I’ll finally get to see what Changes! looks like on the inside,” she said as she put up her hands to surrender.

The SWAT team rushed by her. Within seconds several of them had reached Jane. With practiced movements they grabbed her two wrists, pulled her from her seat, wrenched her arms behind her back, and threw her to the ground. One soldier placed his knee squarely between her shoulders and placed the barrel of a pistol to her head as another soldier bound her wrists with plastic handcuffs. A black bag was placed over her head as she was lifted to her feet.

“Terrorist apprehended, stand down,” a man, evidently their leader, barked into something on his wrist. Immediately the others lowered their weapons.

“Jane?” Xristi ran up to the man in charge and pushed him hard in the chest with both hands. It was like pushing a brick wall. “What the fuck are you goons doing?”

Two soldiers grabbed her immediately, but the leader motioned to them to let her go.

“Ma’am, this is a matter of national security. This person is an enemy combatant. You do your job, we do ours. In fact, we make your job possible. We’ll be out of your way in just a minute and you can resume teaching.”

Xristi looked to the doorway where she had seen Monty Meekman looking through the glass. The door was now open, and the Chancellor stood in the hallway, his face expressionless.

Xristi walked up to him, seething.

“All right. You win. Let her go.”

“Dr. Friedman, you overestimate my authority. I am merely chancellor of the university. I have no say over matters of national security.”

“You let her go this instant, or you can forget your Chronos Collection forever. I’ll unplug it, by Christ I will. I won’t stop until your head collection has melted into a floor covering of slimy, putrid broth. Let her go.”

“So you will assume curatorship of Chronos Collection?”

“What the fuck did I just say, Chancellor.”

“And you’ll stop instructing students?”

“Let her go, you prick.”

Meekman nodded his head nearly imperceptibly, and within seconds the bag had been removed from Jane’s head and she had been released. Although she had been kidnapped for less than two minutes she appeared groggy, as if she had been injected with some kind of drug. She stood, dazed, by the door as the black-clad soldiers emerged from the lecture hall and vanished down the hallway.

In the classroom the telescreens were working once again. On them, Minister of Awareness Ronald Reagan was delivering a reassuring message about keeping the Homeland secure, while Jane’s classmates mutely yielded their intentionality to the technopoly.

In disgust, not only with the students but with herself as well, Xristi turned to Chancellor Meekman and said, “Where you want this thawing done?”

“Follow me,” Meekman said.

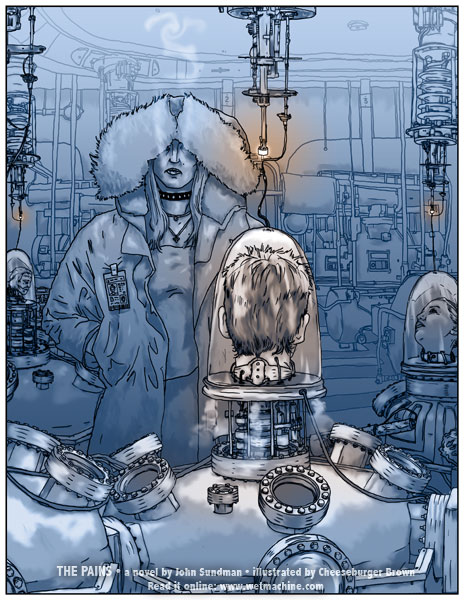

It wasn’t far to go. Down one corridor, another, through a few unmarked doors, down a disused hallway, until they arrived at a door with the word “Chronos” stenciled upon it and six leveraged handles locking it shut. On the wall next to the door hung overcoats, gloves, and knee-high insulated boots. Xristi grabbed an oversized fur-lined parka and put it on. Meekman reached for a coat also, but Xristi slapped his hand.

“I’m going in by myself,” she said.

“Are you quite sure that—“

“I’m the curator, Monty. I make the rules for the Chronos Collection. Now fuck off. Get lost.”

“Are you quite sure that—“

“Fuck off.”

Xristi undid the six clasps. She then slipped her hands into oversized, triply insulated gloves and pulled at a chest-high grip. Slowly the door swung open, revealing a small room that served as an air lock and buffer. Cold air rushed out. At the opposite end was another stenciled, many-handled door. She didn’t know what to expect other than more cold. Would it be like a morgue? A laboratory? She opened the door and stepped into the Chronos Collection.

It was pretty much as she had expected: tubes, pipes, dials, controls, wires, and little bell jars housing frozen heads in deathly unreality. It was gross, obscene, but nothing to really surprise her.

It was pretty much as she had expected: tubes, pipes, dials, controls, wires, and little bell jars housing frozen heads in deathly unreality. It was gross, obscene, but nothing to really surprise her.

Until, that is, she came upon the head of a long-haired man, apparently around thirty years old at the time of his death, with a bright red ring of irritated skin around his neck, almost like a rope burn. Could it be? Really?

She leaned in for a closer look.

And that was when she saw Fred’s lips move.

“Help,” he whispered, his eyes pleading. “Help me to the light.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.