Text Copyright John Sundman 2005

Illustrations Copyright 2005 by Cheeseburger Brown

He first perceived the pain as a toothache in the general area of the upper right quadrant of his mouth. But as he fixed on it and tried to determine which tooth it might be that was hurting, he experienced a swift vague transfer of pain from the upper portion of his mouth—by way of the right side of his neck, down the right side of his body, traversing his torso near his belt line—to a region just north and to the left of his scrotum, where it briefly ceased. Two seconds later he felt the sharp ingrowing of the pinky toenail on his right foot. That pain stopped after about five seconds and was almost immediately replaced by the crushing weight of the white linen sheet under which, exhausted from prayer, Mr. Lux had drifted to sleep only a few hours ago. By faint dawn light, the sheet, where it pressed upon the bad toenail, showed a small bloodstain.

Mr. Lux’s breath was forced from him. The sheet, which still looked as if it were made of white linen, seemingly changed its substance from flax to steel to lead, and now to uranium or even, perhaps, some condensate of neutrons. It weighed tons. Mr. Lux could feel the pressure building in his eyeballs and wondered if they would explode.

There was a burning constriction around his throat. It was as if the Savior’s own noose were tightening, pulling his head up—even as the weight of the sins of the world, transubstantiated into bedclothes, pulled his body down. “Fred, have mercy on me,” Mr. Lux managed to whisper.

The sheet became heavier still. It was pointless for Mr. Lux to try to throw it off: he could no more get free of it than he would have been able to shake himself free of the rubble of an earthquake-collapsed cathedral. And now the toothache was back, and the L-shaped line of fire from his neck to his groin, and the toenail intent on mayhem. His entire body felt crushed, yet each pain was distinct—as if it were an illustration in an anatomy chart, or a highlighted neural pathway in a clear plastic doll.

Mr. Lux knew he should pray, but somehow the pains made prayer impossible. He thought, I am twenty-four years old. I am going to die with my body crushed to liquid and my head neatly garroted off by a thin layer of woven fabric that weighs less than eight ounces. He sensed his mouth moving as if to laugh at the thought, but the laugh was frozen in his immobile torso. Can’t laugh. Can’t breathe. I guess I can’t call for help either. But he could still move his head, which he now did, deliberately, casting his eyes around the sparse cell, nine feet wide by twelve feet long, that had been his home for the last three years.

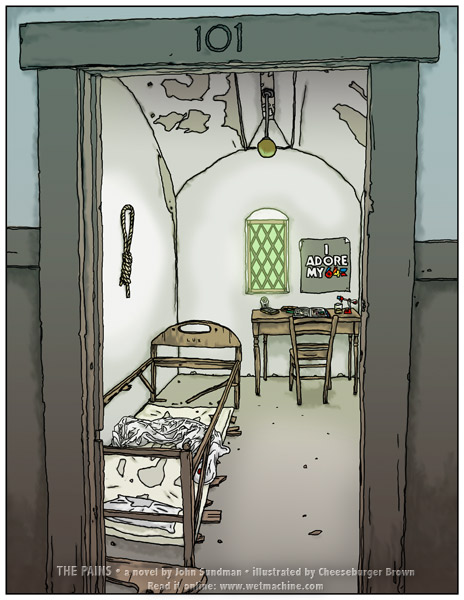

The ancient whitewashed fieldstone walls did not lend themselves to decoration. Centered on one wall, above him and to his left, there was a simple noosifix precariously hanging from an irregularity in a rock. On the opposite wall, to his right, hanging from a nail driven into a chink in the cement, there was a kitschy airbrushed painting of a thatched cottage surrounded by flowers and with a pair of bluebirds sitting at the apex of the roof. In the short wall beyond his feet there was a narrow casement window with diamond-shaped leaded-glass panes through which he could see blurry hints of trees green with tiny leaves of early spring. Below the window were a desk and chair. On the desk: a Holy Tibble; a Fredian missal; copies of Byte, Datamation, and Electrical Engineering Times; a textbook on nonlinear circuits; and one Alfred the Drinking Duck perpetual motion toy.

A monastery cell was an odd place for a young man to live in 1985, Mr. Lux thought as he was dying. Not many people nowadays chose incarceration and self-denial over freedom and pleasure. Simply having religious faith made Mr. Lux something of a weirdo—never mind his living in a nearly abandoned thousand-year-old monastery where the average age of his companions was over seventy. Mr. Lux had known before this morning, of course, that his way of life was odd. But now, suddenly, he really knew it, as if he had just stumbled upon his life from some other, normal, universe, and saw exactly how bizarre it was.

Let’s see.

In Boston, last night, people his age, dressed in blue jeans and sweatshirts, had had pizza for dinner and then gone to smelly punk bars like The Rat and The Channel. There they had consumed beer while having their eardrums assaulted by Mission of Burma or Human Sexual Response. They had danced, shouted short conversations about war and killing over the deafening guitars, laughed, had fun, gone home with friends old or new to messy apartments full of houseplants, record albums, and Penthouse magazines. They had had sex and gone to sleep, without any thoughts in their heads, under the watchful eye of the telescreen, which would have been tuned to The Wee Hours Irony Show.

In New York, last night, people his age, dressed in four-hundred-dollar shirts and six-hundred-dollar slacks, had spent a few hundred dollars each for half-plates of exalted snacks at nouvelle cuisine places on Wall Street. Then they had gone to parties in lofts in SoHo, where they had consumed champagne while discussing how war was a good time for making money. They had gone home with friends old or new to four-thousand-square-foot Tribeca apartments impeccably decorated in the retro-modernist style. They had had sex and gone to sleep, without any thoughts in their heads, under the watchful eye of the telescreen, which would have been tuned to The Wee Hours Irony Show.

In McKinley DC, last night, people his age, wearing conventional clothes, had eaten conventional food and consumed alcohol. They had talked about the Party and its latest strategy for marketing the war to the proles outside the Beltway. They had had sex and gone to sleep, without any thoughts in their heads, under the watchful eye of the telescreen, which would have been tuned to The Wee Hours Irony Show.

Mr. Lux, on the other hand, last night had had a meal of cold porridge with bony fish and turnips, which he ate, in silence, in the company of other men dressed in long black cassocks like the one that he himself wore. After dinner he had gone to the chapel for prayers. After prayers he had gone to the lounge for half an hour of social time, during which he had discussed Aristotelian metaphysics with an earnest newly minted priest from Hong Kong. Then he had gone back to his room, studied his textbook on nonlinear circuits for two hours, daydreamed about getting his hands on an Atari motherboard and overclocking it, kneeled at his bed and prayed for an hour meditating on the mystery of the noose, gone to sleep for three hours with his head full of thoughts about electrical circuits and redemption, and, right about the moment when other young men all over Freemerica—from Texas to New Kent to Massachusetts, were having the first of their orgasms for the night, Mr. Lux, a celibate novitiate in the Society of Fred, was sleepily padding down a candlelit corridor, passing one after another empty dormitory room, heading back to the chapel for the Dark Hours prayers.

Studying for the priesthood in this day and age was odd enough. But even among religious people his monastic way of life was considered perversely archaic. Other orders had accommodated themselves to changing times, found ways to train Fredian priests without making them live in some mediaeval theme park. Most priests nowadays lived among the proles. Like everybody else, priests had apartments with telescreens on which they watched Diff’rent Strokes, Happy Facts with Oliver North, and Fantasy Island; they lived in the material world, as Madonna put it. Unlike members of the Society of Fred, whose training period before ordination lasted seven years—seven years of prayerful contemplation of the Holy Tibble and the life and teachings of Fred, the Savior—most modern priests were ordained after only one year of “theological” study—and at least two-thirds of their curriculum was not based on the study of ancient texts, but on a modern spirituality of massage therapy, pyramid power, and the godhead of aroma. Moreover, mainstream priests like Peterists and Delmonicans had long ago stopped regarding the idea of sexual restraint as anything but a quaint throwback to a superstitious time. It wasn’t entirely unlikely that a young Peterist or Delmonican had cruised The Rat last night and gone home lucky.

Mr. Lux, on the other hand, had joined the retrograde and severe Society of Fred, “the Freduits,” and spent much of his time in sexually deprived silence at the Monastery of Saint Reinhold, where time more or less stood still.

But he wasn’t a prisoner there: three days per week Mr. Lux left the monastery for a few hours to attend classes in electrical engineering at the University of New Kent, and two days each week he ministered to guests at Changes!, the Ministry of Love’s maximum-security correctional home. But even when out of the monastery, “in the World”, Mr. Lux wore the modified cassock that announced his Freduit vocation for all to see (and ridicule). And as for chastity: well, he had lost his virginity when he was nineteen, at the insistence of his then-girlfriend Nancy, and had spent the several weeks following the loss of virginity in essentially nonstop fucking, which he greatly enjoyed. So chastity for Mr. Lux was more than a theoretical sacrifice. A few months after initiating Norman into the pleasures of the flesh, however, Nancy had been drafted into the Peace Force, and almost immediately thereafter she had been reported missing and presumed drowned when her troopship went down in the Sea of Kentucky. The very day after learning of the death of his love Nancy, Mr. Lux had received a mystical vocation, joined the Society, and taken the vow of Seven Years Waiting. Now he was in the fourth year of his seven-year program of study, and the next social orgasm he could look forward to was three years away.

To be precise, that anticipated social orgasm that would sanctify his ordination was three years, two months, and three days away. Of course, unless something changed soon he wasn’t going to live to experience it. He didn’t expect to live more than another minute, actually. Three years sure is a long time to go without breathing, Mr. Lux thought. His field of vision was narrowing; darkness was coming from all sides. It wasn’t the dying that bothered him so much, he realized, it was dying before ordination, having never felt the Vestal Tug. All that horniness wasted, with no spiritual benefit to anyone, least of all himself.

Sweat was pouring from every pore in his body, burning his eyes, soaking his mattress. What was causing all this agony? He had experienced painful fevers before, but nothing so sudden, nothing that mixed a toothache with an ingrown toenail with nuts in a vise. At last a prayer escaped his lips: Oh my Fred, I am dying, have mercy! And then, in a sudden crisp moment he thought, Might this be The Pains?

“Arrrgh!” he bellowed, screaming like an air raid siren. His bed collapsed underneath him, crashing to the floor, the ancient wood in splinters.

From this new, lower angle he looked out through the window at blue sky. All pain was gone. For a full minute he lay without moving on his cold, sweat-soaked mattress, overjoyed at the palpable lightness of the sheet, the absence of toothache, the toe that had nothing to say, the breath that went in and out as if breathing were the most natural thing in the world. How long had his ordeal lasted? One minute? Two at the most? It had seemed endless, each second a century, and yet the painless seconds raced by. He smiled at this insight into the elasticity of perceived time.

And then he heard voices, and running in the hallway. Cries of Norman! Norman!

His door swung open and his four classmates tumbled into the room—Messrs. Chen, Agnolli, LaFont, and Powers—these four who were, besides Norman, the entire future of the Society of Fred, which used to ordain a hundred Freduits each year from Saint Reinhold’s alone, centuries ago when Reinhold’s was only one among dozens of such monasteries. They stood breathless in an arc around his bed, cassocks half-fastened, noosifixes still swinging around their necks, looking down in silent awe. Another fast minute sped by.

“Fred Christ,” somebody said finally, and they all giggled.

Then Mr. Lux heard another set of footsteps approaching down the corridor. The Old Man, he thought. The Old Man must be coming.

“What’s this?” came a deep voice. “Stand back please.” The Korloonian accent was thick.

Mr. Lux still had not moved since the complex of pains had miraculously disappeared. He was aware that he was lying on his broken bed and that the abbot had just entered the room, but he was strangely content to do nothing. He thought that maybe he should rise as a sign of respect, but before he could decide whether to do that the abbot Fr. Hessberg was looming over him—six feet four inches of ex-boxer topped by another four inches of Einstein-wild hair.

“Are you all right?”

“Yes, Abbot, I think so,” said Mr. Lux. “Yes, I’m fine.”

“What happened here? How did the bed break?”

“I don’t know.”

Father Hessberg thought about that for a moment.

“Were you alone?” he asked, with his accent sounding more pronounced than ever. His blue eyes seemed to Mr. Lux as if they would bore through him.

“Yes, Father. I was alone.”

The abbot and the novitiate stared at each other for another few moments, until Fr. Hessberg stepped back, looked to his left and right at the other novitiates, and said, “It looks like Mr. Lux has been dreaming about the Vestal Virgins again. Don’t worry, Norman, your tug will come.”

Mr. Lux smiled and the four others laughed nervously.

“Gentlemen, thank you for your concern. You may go back to your business,” the abbot said, “quietly.” Mr. Chen, Mr. Agnolli, Mr. LaFont and Mr. Powers meekly left the room, presumably to return to their cells for private prayer and reflection until it was time for ablutions and breakfast.

Norman Lux still had not moved other than to speak. Now Fr. Hessberg knelt on the cold flagstone floor. He felt the sheet, which was quite drenched where it rested on Mr. Lux’s body. He smelled his finger, and then turned his attention to the penny-sized bloodstain over Mr. Lux’s right pinky toe.

“Mr. Lux, please go to the infirmary, and I will have Father Doyle meet you there. I am hoping that he will determine that you are well. If he does so, please join me in my study after matins.”

“Yes, Father Abbot,” Mr. Lux said. The abbot was already halfway out the room.

Father Doyle’s examination was perfunctory and the results unremarkable. Perhaps Fr. Doyle would have taken a little more time if Mr. Lux had volunteered a little more information about what he had experienced. But Fr. Doyle asked little, Mr. Lux told less, and ten minutes after the examination had begun, the patient was declared hale.

“Nothing a cold bath won’t cure,” Fr. Doyle said.

Cold bath? The bath was beyond cold; it was freezing. Nevertheless it was barely having the beneficial effect to which he presumed Fr. Doyle had alluded. For although Norman Lux had gone through most of last week without giving more than a passing thought to his future ordination and the Rite of the Vestals that would consecrate it, now that Fr. Abbot and Fr. Doyle had put the thought into his head he was having a difficult time putting it out of his mind. And out of his . . . well . . . But eventually, when he was sure he was on the edge of hypothermia, the hot blood quieted and his thoughts turned from the Virgins to his odd experience of just an hour ago.

He returned from the baths to his room, where he found that his broken bed had been replaced by a structurally sound one and made up with fresh linens. He quickly dressed in loose black pants and handwoven white shirt, over which he put his spare black cassock. He went to the window and pushed it open. Smells of breakfast wafted up from the kitchen one floor down. Birds chirped. It was good to be alive, Mr. Lux thought, even if he was about to go have a chat with the Old Man, something most residents of Saint Reinhold’s relished as much as they did a visit to the tooth doctor. He made a quick sign of the noose and strode purposefully out of his room.

The route to the abbot’s study took him down long dark corridors. From his room in the Old Dormitory made of stone he walked up the tower stairs to a newer wing made of brick. Newer, but still old, and just as vacant. But though most of the rooms in every wing of the monastery were empty—more than one thousand empty rooms—and although all of its hundreds of hallways were only dimly illuminated, yet Saint Reinhold’s was anything but decrepit. The monastery was immaculately clean; the floors even shone. The Freduits gave no indication that they had noticed their order was dying out. If a hundred recruits were to show up tomorrow the monastery could handle the influx with no problem. The Society of Fred, an obscure dying order in a dying church, simply refused to acknowledge that the world no longer needed or wanted it—if it ever had.

Once again Mr. Lux experienced the clear realization that he had had when his sheet was crushing him to death just a little while ago, the profound awareness of how odd was his monastic lifestyle. And yet he felt perfectly at home here, could imagine living nowhere else. He realized that he was actually looking forward to going to see the Old Man.

“Come in,” Fr. Hessberg said. “Take a seat.”

The abbot sat in a giant wooden chair behind an enormous wooden desk. He indicated a small wooden stool on the opposite side of the desk. Mr. Lux sat.

“Well?” the abbot said.

“Yes, Father Abbot?”

“What happened to you this morning? I want to know everything.”

And so Mr. Lux told him, as accurately as he could, about how he had awakened. He told him about the tooth pain, the toenail pain, the migrating pains—even about his imagining himself an anatomy doll. Father Hessberg said nothing, merely regarded Norman Lux with those intense blue eyes.

“Is that all?” the abbot finally said.

“Father?”

“Yes, son?”

Mr. Lux hesitated. He knew that there might be severe consequences for what he was about to say. Consequences, perhaps, such as being asked to leave the Society of Fred. But it was the truth, and the truth would set him free.

“I had the strong sense that the pain in my body might have been a soul gone bad,” he said, and drew in his breath like a child expecting a spanking.

But the reaction of the abbot was not severe or chagrined. In fact, Mr. Lux had the impression that this confession was the single thing that Fr. Hessberg had been waiting to hear, that everything that had happened since the Old Man had knelt by Mr. Lux’s bed until now had merely been a patient exercise to get Mr. Lux to volunteer this fact.

“Ah, so.” Father Hessberg said. “Just so. You think it might have been The Pains.”

“Yes, Father.”

The abbot looked distracted, as if he were thinking of something far off. Without seeming to pay much attention to what he was doing, he opened a drawer in his desk from which he withdrew what appeared to be a thick dowel of dark wood and a small knife with an ivory handle. He began to whittle, without looking at his hands.

“You are in your fourth year here, is that correct?”

The abbot obviously knew it was correct. It wasn’t as if the abbot of Saint Reinhold’s were the registrar at the University of New Kent, where there were thousands of students in each class. The abbot of Saint Reinhold’s had only had five recruits in the last four years.

“Yes, Father.”

“Father Murray is your instructor in metaphysics?”

The abbot knew that too.

“Yes.”

“The Pains is a fairly abstruse subject. I’ve been a Freduit for fifty-four years, and I’ve never heard of a confirmed case of The Pains. So you can see why it’s not a subject that is covered in introductory courses. The Pains is a very rare condition. You understand that don’t you?”

“Of course, sir.”

“When did you first encounter the theology of The Pains? Was it recently?”

Now that you mention it . . . Mr. Lux’s confidence seemed to diminish a few notches.

“Why, yes Father. It was last week,” Mr. Lux said.

“Tell me, son, what is your understanding? What are The Pains?”

“One person experiences physical torment in proportion to the danger to another person’s soul.”

“And?”

“And the fate of the world is tied to the fate of the person whose soul is in danger,” Mr. Lux added, somewhat sheepishly. “And commutatively to the Painee.”

“So the person who experiences The Pains can only save himself if he saves the endangered soul and thereby saves the world. Is that right? He is a kind of savior?”

“Yes, Father.” He could see where this was going, and felt himself blushing.

“And what is the correlation between this endangered soul and the person with The Pains? How does one relate to the other? What is the cause and effect? In other words, why do The Pains descend upon one particular person, for example, upon you instead of me?”

“Nobody knows,” Mr. Lux said.

And then Mr. Lux really put his foot in it, responded without thinking. He blurted out an idea that he had been carrying around for a week without even realizing how much he had been brooding about it.

“I don’t think it is a matter of cause and effect, Father Abbot. I think it has to do with chaos theory.”

“Chaos theory!” the abbot laughed. He placed the knife and stick of wood, which appeared to be taking the shape of—what? A boat?—on the desk.

Whereas all morning, until this instant, Fr. Hessberg had been playing to the hilt the role of stereotypic Korloonian—intense, no nonsense—now he laughed as if he had never seen such a funny thing in his life: a fourth-year Freduit novitiate, hornier than a herd of rhinoceri, learns about The Pains in his metaphysics class and one week later becomes convinced that he’s the One to save the world, thinking it has to do with some new kind of funny math.

“Chaos theory!” and the priest gagged on his laughter and slapped the desk. Tears were streaming down his face. Eventually he got his composure back, at least partially.

“Well that’s the one thing I love about Father Murray,” the abbot continued. The strain of not laughing was nearly too much for him. “When he teaches metaphysics, by Fred he makes it real. He makes a believer out of you!”

“Yes, Father,” Mr. Lux said. Why had he ever thought that coming to the Old Man’s office would be an OK thing to do? What had he been thinking? Whatever little bits of self-confidence he had had when entering the abbot’s study had vanished. A moment ago he had been willing to bet his vocation, and now he felt like an idiot.

“Mr. Lux, tell me about your job.”

“My job, Father?”

“Yes. Your job. You have started working in the chaplaincy at the prison, have you not? The prison the, the, the . . . what do they call it now?”

“Compassionate care facility,” Mr. Lux said. “It’s been privatized. They call it Changes, with an explanation point,” he said, then added with emphasis, “Changes!”

The abbot didn’t appear to be listening to him.

“Do you know, Mr. Lux, what is the chief medical complaint of medical students?”

“Sir?”

“Medical students. What diseases they get while in medical school? You don’t know? I will tell you. Whatever one they are studying that they have never heard of before. They read about the symptoms, and the next thing you know they experience them. Do you like working at the prison?”

“Well, Father, I—“

“We had another seminarian here not too long ago. An extraordinary student, actually. Ferocious faith. Horatio Norton, his name. He too once thought he had The Pains. He’s now a prisoner there, a—what do they call them now?”

“Guests?”

“Yes, a ‘guest,’” the abbot sneered. “He was convicted of selling Freemerican secrets, military secrets, to my home country, Korloon, in Eastasia, with whom Freemerica now plans to go to war. Did you know I was Korloonian?”

Mr. Lux had heard that the abbot could sometimes work himself into a frenzy, but in four years had never heard him raise his voice. In fact, Mr. Lux had never seen him more agitated than he appeared to be right now. Father Hessberg got up from his chair and paced his candlelit study.

“Yes, Father, I had heard—“ Mr. Lux started to say.

“This seminarian, this prisoner, Norton, what do they call him?”

Should Mr. Lux admit that he knew of this ex-Freduit? It seemed a hot topic, perhaps one best avoided for now.

“What they call him, Father?” Mr. Lux said, feigning ignorance.

“Do not play games with me, child!” Father Hessberg shouted. “You know very well what I mean. What is the appellation they have given him?”

It was no good playing dumb.

“Father Abbot, sir, they call him the Eagle.”

“Yes, yes!” said Fr. Hessberg, lowering his voice. “The Eagle. Let me ask you, did he ask to speak to a chaplain last week? To meet with you?”

“Yes, Father.”

“Well. So. That is the first time he has asked to see a chaplain in six years. Did you speak with him?”

How did Fr. Hessberg know that the Eagle had not spoken to a chaplain in six years? How did he know that Mr. Lux had spoken with him last week?

“Yes,” Mr. Lux said.

“For how long?”

“About ten minutes.”

“About what did you speak?”

“Small talk. The weather. Caring-facility food.”

“Not about The Pains?”

“Oh no sir, never. We didn’t talk about anything remotely metaphysical.”

“He will want to, you know,” Fr. Hessberg said. “He will certainly want to discuss metaphysics with you. He is a very gifted debater too. Very subtle. Mr. Lux, what do you think of the Party?”

“The Party, Father?” Father Hessberg jumped from one topic to another as if there were a logic he could see that was completely invisible to Mr. Lux.

“Come, come, son. I am your abbot. Big Brother does not come within the walls of Saint Reinhold’s. There are no telescreens here. You can speak freely to me. You do not need to fear the Party here.”

“Well then, sir, I think the Party is an abomination.”

“And so it is. But not everyone that the Party convicts of a crime and sends to prison is innocent. Remember that. This ‘Eagle’ will soon want to discuss theology with you, and as chaplain it will be your duty to minister to him. Do you understand what that means?”

“Yes, I hope so.”

“You must bear witness to Fred who was hanged in the noose!” the abbot exclaimed. “This is a responsibility you cannot avoid, although I wish I could go in your place. This man, this ‘Eagle,’ is a danger to your soul, Mr. Lux. Be very careful.”

“Yes, sir.” Mr. Lux felt a sudden coldness all through him, as if he were back in Fr. Doyle’s ice bath.

“Mr. Lux, look at me.”

The abbot’s eyes blazed blue fire.

“Mr. Lux, you do not have The Pains. The Pains is a rare condition unseen on Earth for more than two hundred years. It is natural for you to have thought that you did. It happens to many seminarians. It happened to me. But I did not have The Pains, nor did the Horatio Norton have The Pains. And you do not have The Pains. Now, repeat after me: ‘I do not have The Pains.’”

“I do not have The Pains,” Mr. Lux said, without conviction.

“But perhaps by the time your study here has concluded, you will wish that you did have them. Come, stand up. We must go to the chapel. It is time for prayers.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.